It is hard to find good analogies for running a startup that founders can learn from. Some of the typical comparisons — playing competitive sports & games, working on large projects, running large organizations — all fall short of capturing the feeling that the odds are stacked against you that founders have to grapple with.

But the annals of military history offer a surprisingly good analogy to the startup grind. Consider the campaigns of some of history’s greatest military leaders — like Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar — who successfully waged offensive campaigns against numerically superior opponents in hostile territory. These campaigns have many of the same hallmarks as startups:

- Bad odds: Just as these commanders faced superior enemy forces in hostile territory, startups compete against incumbents with vastly more resources in markets that favor them.

- Undefined rules: Unlike games with clear rules and a limited set of moves, military commanders and startup operators have broad flexibility of action and must be prepared for all types of competitive responses.

- Great uncertainty: Not knowing how the enemy will act is very similar to not knowing how a market will respond to a new offering.

As a casual military history enthusiast and a startup operator & investor, I’ve found striking parallels in how history’s most successful commanders overcame seemingly insurmountable odds with how the best startup founders operate, and think that’s more than a simple coincidence.

In this post, I’ll explore the strategies and campaigns of 9 military commanders (see below) who won battle after battle against numerically superior opponents across a wide range of battlefields. By examining their approach to leadership and strategy, I found 5 valuable lessons that startup founders can hopefully apply to their own ventures.

| Leader | Represented | Notable Victories | Legacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander the Great | Macedon (336-323 BCE) | Tyre, Issus, Gaugamela, Persian Gate, Hydapses | Conquered the Persian Empire before the age of 32; spread Hellenistic culture across Eurasia and widely viewed in the West as antiquity’s greatest conqueror |

| Hannibal Barca | Carthage (221-202 BCE) | Ticinus, Trebia, Trasimene, Cannae | Brought Rome the closest to its defeat until its fall in 5th century CE; he operated freely within Italy for over a decade |

| Han Xin (韓信) | Han Dynasty (漢朝) (206-202 BCE) | Jingxing (井陘), Wei River (濰水), Anyi (安邑) | Despite being a commoner, his victories led to the creation of the Han Dynasty (漢朝) and his being remembered as one of “the Three Heroes of the Han Dynasty” (漢初三傑) |

| Gaius Julius Caesar | Rome (59-45 BCE) | Alesia, Pharsalus | Established Rome’s dominance in Gaul (France); became undisputed leader of Rome, effectively ending the Roman Republic, and his name has since become synonymous with “emperor” in the West |

| Subutai | Mongol Empire (1211-1248) | Khunan, Kalka River, Sanfengshan ( 三峰山), Mohi | Despite being a commoner, became one of the most successful military commanders in the Mongol Empire. Successfully won battles in more theaters than any other commander (China, Central Asia, and Eastern Europe) |

| Timur | Timurid Empire (1370-1405) | Kondurcha River, Terek River, Dehli, Ankara | Created Central Asian empire with dominion over Turkey, Persia, Northern India, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia. His successors would eventually create the Mughal Empire in India which continued until the 1850s |

| John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough | Britain (1670-1712) | Blenheim, Ramillies | Considered one of the greatest British commanders in history; Paved the way for Britain to overtake France as the pre-eminent military and economic power in Europe |

| Frederick the Great | Prussia (1740-1779) | Hohenfriedberg, Rossbach, Leuthen | Established Prussia as the pre-eminent Central European power after defeating nearly every major European power in battle; A cultural icon for the creation of Germany |

| Napoleon Bonaparte | France (1785-1815) | Rivoli, Tarvis, Ulm, Austerlitz, Jena-Auerstedt, Friedland, Dresden | Established a French empire with dominion over most of continental Europe; the Napoleonic code now serves as basis for legal systems around the world and the word Napoleon synonymous with military genius and ambition |

Before I dive in, three important call-outs to remember:

- Running a startup is not actually warfare — there are limitations to this analogy. Startups are not (and should not be) life-or-death. Startup employees are not bound by military discipline (or the threat of imprisonment if they are derelict). The concept of battlefield deception, which is at the heart of many of the tactics of the greatest commanders, also doesn’t translate well. Treating your employees / co-founders as one would a soldier or condoning violent and overly aggressive tactics would be both an ethical failure and a misread of this analogy.

- Drawing lessons from these historical campaigns does not mean condoning the underlying sociopolitical causes of these conflicts, nor the terrible human and economic toll these battles led to. Frankly, many of these commanders were absolutist dictators with questionable motivations and sadistic streaks. This post’s focus is purely on getting applicable insights on strategy and leadership from leaders who were able to win despite difficult odds.

- This is not intended to be an exhaustive list of every great military commander in history. Rather, it represents the intersection of offensive military prowess and my familiarity with the historical context. Just because I did not mention a particular commander has no bearing on their actual greatness.

With those in mind, let’s explore how the wisdom of historical military leaders can inform the modern startup journey. In the post, I’ll unpack five key principles (see below) drawn from the campaigns of history’s most successful military commanders, and show how they apply to the challenges ambitious founders face today.

| 1. Get in the trenches with your team |

| 2. Achieve and maintain tactical superiority |

| 3. Move fast and stay on offense |

| 4. Unconventional teams win |

| 5. Pick bold, decisive battles |

Principle 1: Get in the trenches with your team

One common thread unites the greatest military commanders: their willingness to share in the hardships of their soldiers. This exercise of leadership by example, of getting “in the trenches” with one’s team, is as crucial in the startup world as it was on historical battlefields.

Every commander on our list was renowned for marching and fighting alongside their troops. This wasn’t mere pageantry; it was a fundamental aspect of their leadership style that yielded tangible benefits:

- Inspiration: Seeing their leader work shoulder-to-shoulder with them motivated soldiers to push beyond their regular limits.

- Trust: By sharing in their soldiers’ hardships, commanders demonstrated that they valued their troops and understood their needs.

- Insight: Direct involvement gave leaders firsthand knowledge of conditions on the ground, informing better strategic decisions.

Perhaps no figure exemplified this better than Alexander the Great. Famous for being one of the first soldiers to jump into battle, Alexander was wounded seriously multiple times. This shared experience created a deep bond with his soldiers, culminating in his legendary speech at Opis where he was able to quell a mutiny of his soldiers, tired after years of campaigns, with a speech reminding them of their shared experiences:

The wealth of the Lydians, the treasures of the Persians, and the riches of the Indians are yours; and so is the External Sea. You are viceroys, you are generals, you are captains. What then have I reserved to myself after all these labors, except this purple robe and this diadem? I have appropriated nothing myself, nor can any one point out my treasures, except these possessions of yours or the things which I am guarding on your behalf. Individually, however, I have no motive to guard them, since I feed on the same fare as you do, and I take only the same amount of sleep.

Nay, I do not think that my fare is as good as that of those among you who live luxuriously; and I know that I often sit up at night to watch for you, that you may be able to sleep.

But some one may say, that while you endured toil and fatigue, I have acquired these things as your leader without myself sharing the toil and fatigue. But who is there of you who knows that he has endured greater toil for me than I have for him? Come now, whoever of you has wounds, let him strip and show them, and I will show mine in turn; for there is no part of my body, in front at any rate, remaining free from wounds; nor is there any kind of weapon used either for close combat or for hurling at the enemy, the traces of which I do not bear on my person.

For I have been wounded with the sword in close fight, I have been shot with arrows, and I have been struck with missiles projected from engines of war; and though oftentimes I have been hit with stones and bolts of wood for the sake of your lives, your glory, and your wealth, I am still leading you as conquerors over all the land and sea, all rivers, mountains, and plains. I have celebrated your weddings with my own, and the children of many of you will be akin to my children.

Alexander the Great (as told by Arrian)

This was not unique to Alexander. Julius Caesar famously slept in chariots and marched alongside his soldiers. Napoleon was called “le petit caporal” by his troops after he was found sighting the artillery himself, a task that put him within range of enemy fire and was usually delegated to junior officers.

Frederick the Great also famously mingled with his soldiers while on tour, taking kindly to the nickname from his men, “Old Fritz”. Frederick understood the importance of this as he once wrote to his nephew:

“You cannot, under any pretext whatever, dispense with your presence at the head of your troops, because two thirds of your soldiers could not be inspired by any other influence except your presence.”

Frederick the Great

Image credit: WikiMedia Commons

For Startups

For founders, the lesson is clear: show up when & where your team is and roll up your sleeves so they can see you work beside them. It’s not just that startups tend to need “all hands on deck”, but being in the trenches also provides “on the ground” context that is valuable and help create the morale needed to succeed.

Elon Musk, for example, famously spent time on the Tesla factory floor — even sleeping on it — while the company worked through issues with its Model 3 production, noting in an interview:

“I am personally on that line, in that machine, trying to solve problems personally where I can,” Musk said at the time. “We are working seven days a week to do it. And I have personally been here on zone 2 module line at 2:00 a.m. on a Sunday morning, helping diagnose robot calibration issues. So I’m doing everything I can.”

Principle 2: Achieve and maintain tactical superiority

To win battles against superior numbers requires a commander to have a strong tactical edge over their opponents. This can be in the form of a technological advantage (i.e. a weapons technology) or an organizational one (i.e. superior training or formations), but these successful commanders always made sure their soldiers could “punch above their weight”.

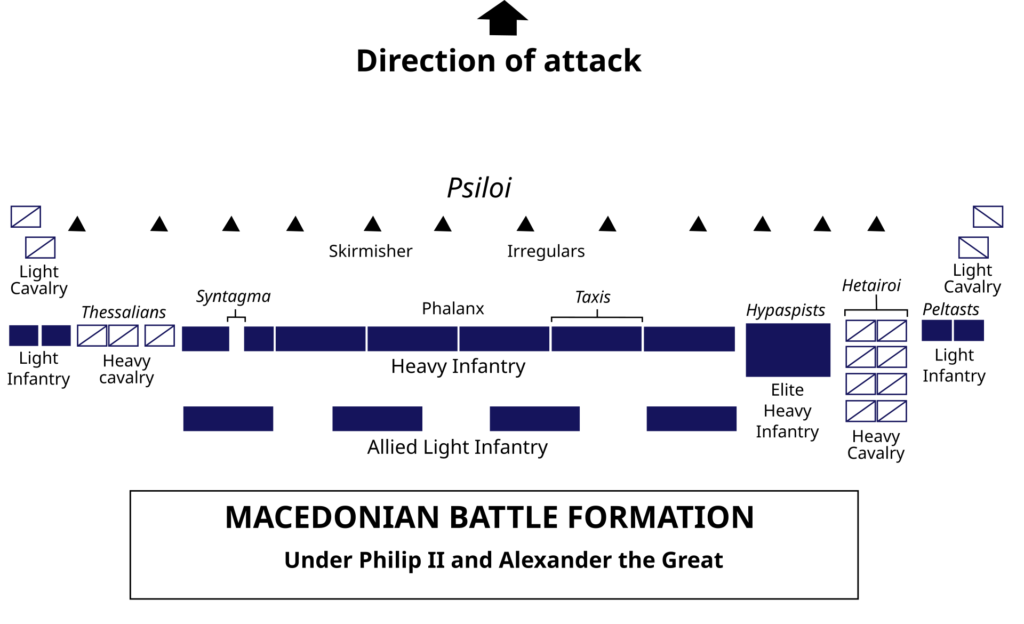

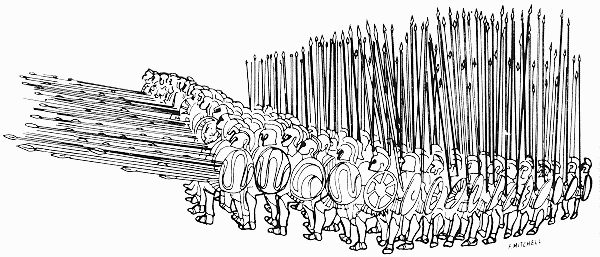

Alexander the Great, for example, leveraged the Macedonian Phalanx, a modification of the “classical Greek phalanx” used by the Greek city states of the era, that his father Philip II helped create.

The formation relied on “blocks” of heavy infantry equipped with six-meter (!!) long spears called sarissa which could rearrange themselves (to accommodate different formation widths and depths) and “pin” enemy formations down while the heavy cavalry would flank or exploit gaps in the enemy lines. This formation made Alexander’s army highly effective against every military force — Greeks, Persians, and Indians — it encountered.

A few centuries later, the brilliant Chinese commander Han Xin (韓信) leaned heavily on the value of military engineering. Han Xin (韓信)’s soldiers would rapidly repair & construct roads to facilitate his army’s movement or, at times, to deceive his enemies about which path he planned to take. His greatest military engineering accomplishment was at the Battle of Wei River (濰水) in 204 BCE. Han Xin (韓信) attacked the larger forces of the State of Qi (齊) and State of Chu (楚) and immediately retreated across the river, luring them to cross. What his rivals had not realized in their pursuit was that the water level of the Wei River was oddly low. Han Xin (韓信) had, prior to the attack, instructed his soldiers to construct a dam upstream to lower the water level. Once a sizable fraction of the enemy’s forces were mid-stream, Han Xin (韓信) ordered the dam released. The rush of water drowned a sizable portion of the enemy’s forces and divided the Chu (楚) / Qi (齊) forces letting Han Xin (韓信)’s smaller army defeat and scatter them.

A century and a half later, Roman statesman and military commander Gaius Julius Caesar also famously advocated military engineering capability in his wars with the Germanic tribes in Gaul. He became the first Roman commander to cross the Rhine (twice!) by building bridges to make the point to the Germanic tribes that he could invade them whenever he wanted. At the Battle of Alesia in 52 BCE, after trading battles with the skilled Gallic commander Vercingetorix who had united the tribes in opposition to Rome, Caesar besieged Vercingetorix’s fortified settlement of Alesia while simultaneously holding off Gallic reinforcements. Caesar did this by building 25 miles of fortifications surrounding Alesia in a month, all while outnumbered and under constant harassment from both sides by the Gallic forces! Caesar’s success forced Vercingetorix to surrender, bringing an end to organized resistance to Roman rule in Gaul for centuries.

The Mongol commander Subutai similarly made great use of Mongol innovations to overcome defenders from across Eurasia. The lightweight Mongol composite bow gave Mongol horse archers a devastating combination of long range (supposedly 150-200 meters!) and speed (because they were light enough to be fired while on horseback). The Mongol horses themselves were another “biotechnological” advantage in that they required less water and food which let the Mongols wage longer campaigns without worrying about logistics.

In the 18th century, Frederick the Great transformed warfare on the European continent with a series of innovations. First, he drilled his soldiers stressing things like firing speed. It is said that lines of Prussian riflemen could fire over twice as fast as other European armies they faced, making them exceedingly lethal in combat.

Frederick was also famous for a battle formation: the oblique order. Instead of attacking an opponent head on, the oblique order involves confronting the enemy line at an angle with soldiers massed towards one end of the formation. If one’s soldiers are well-trained and disciplined, then even with a smaller force in aggregate, the massed wing can overwhelm the opponent in one area and then flank or surround the rest. Frederick famously boasted that the oblique order could allow a skilled force to win over an opposing one three times its size.

Finally, Frederick is credited with popularizing horse artillery, the use of horse-drawn light artillery guns, in European warfare. With horse artillery units, Frederick was able to increase the adaptability of his forces and their ability to break through even numerically superior massed infantry by concentrating artillery fire where it was needed.

A few decades later, Napoleon Bonaparte became the undisputed master of much of continental Europe by mastering army-level logistics and organization. While a brilliant tactician and artillery commander, what set Napoleon’s military apart was its embrace of the “corps system”, which subdivided his forces into smaller, self-contained corps that were capable of independent operations. This allowed Napoleon the ability to pursue grander goals, knowing that he could focus his attention on the most important fronts of battle, while the other corps could independently pin an enemy down or pursue a different objective in parallel.

Additionally, Napoleon invested heavily in overhauling military logistics, using a combination of forward supply depots and teaching his forces to forage for food and supplies in enemy territory (and, just as importantly, how to estimate what foraging can do to help determine the necessary supplies to take). This investment led to the invention of modern canning technology, first used to support the marches of the French Grande Armée. The result was Napoleon could field larger armies over longer campaigns all while keeping his soldiers relatively well-fed.

For Startups

Founders need to make sure they have a strong tactical advantage that fits their market(s). As evidenced above, it does not need to be something as grand as an unassailable advantage, but it needs to be a reliable winner and something you continuously invest in if you plan on competing with well-resourced incumbents in challenging markets.

The successful payments company Stripe started out by making sure they would always win on developer ease of use, even going so far as to charge more than their competition during their Beta to make sure that their developer customers were valuing them for their ease of use. Stripe’s advantage here, and continuous investment in maintaining that advantage, ultimately let it win any customer that needed a developer payment integration, even against massive financial institutions. This advantage laid the groundwork for Stripe’s meteoric growth and expansion into adjacent categories from its humble beginnings.

Principle 3: Move fast and stay on offense

In both military campaigns and startups, speed and a focus on offense plays an outsized role in victory, because the ability to move quickly creates opportunities and increases resiliency to mistakes.

Few understood this principle as well as the Mongol commander Subutai who frequently took advantage of the greater speed and discipline of the Mongol cavalry to create opportunities to win.

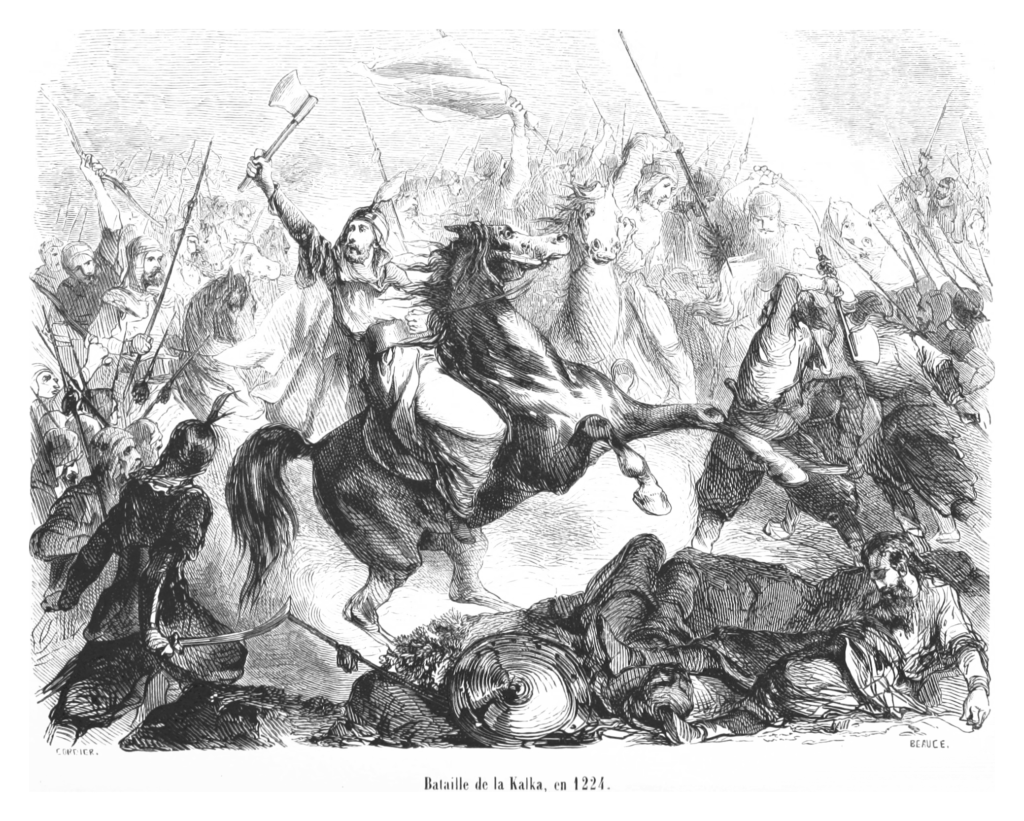

In the Battle of the Kalka River (1223), Subutai took what initially appeared to be a Mongol defeat — when the Kievan Rus and their Cuman allies successfully entrapped the Mongol forces in the area — and turned it into a victory. The Mongols began a 9 day feigned retreat (many historians believe this was a real retreat that Subutai turned into a feigned one once he realized the situation), constantly tempting the enemy by staying just out of reach into overextending themselves in pursuit.

After 9 days, Subutai’s forces took advantage of their greater speed to lay a trap. Once the Mongols crossed the river they reformed their lines to lie in ambush. As soon as the Rus forces crossed the Kalka River, they found themselves surrounded and confronted with a cavalry charge they were completely unprepared for. After all, they had been pursuing what they thought was a fleeing enemy! Their backs against the river, the Rus forces (including several major princes) were annihilated.

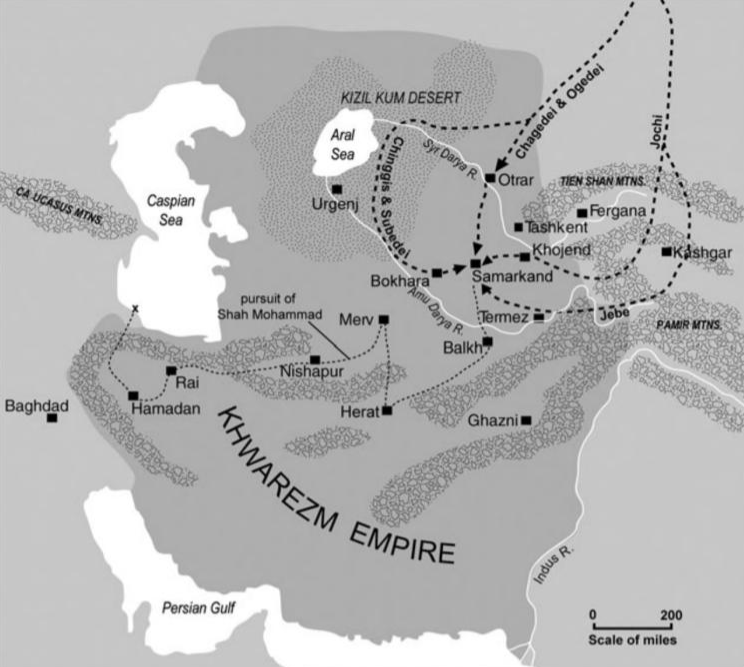

Subutai took advantage of the Mongol speed advantage in a number of his campaigns, coordinating fast-moving Mongol divisions across multiple objectives. In its destruction of the Central Asian Khwarazmian empire, the Mongols, under the command of Subutai and Mongol ruler Genghis Khan, overwhelmed the defenders with coordinated maneuvers. While much of the Mongol forces attacked from the East, where the Khwarazmian forces massed, Subutai used the legendary Mongol speed to go around the Khwarazmian lines altogether, ending up at Bukhara, 100 miles to the West of the Khwarazmian defensive position! In a matter of months, the empire was destroyed and its rulers chased out, never to return.

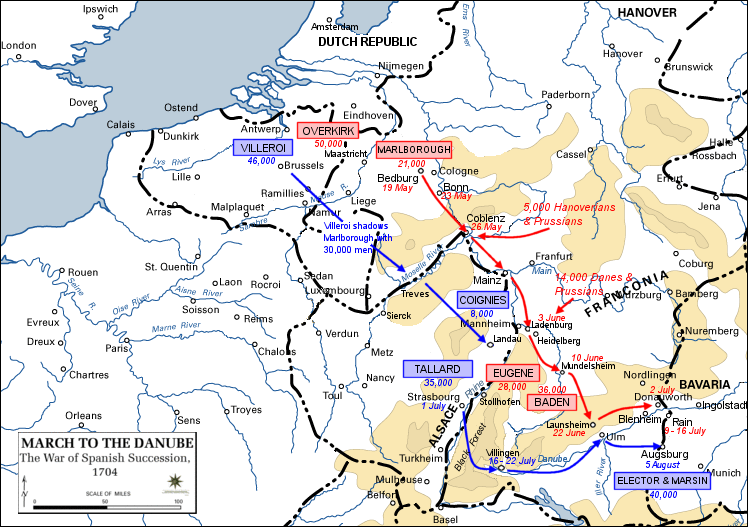

A few hundred years later, the Englishman John Churchill, the Duke of Marlborough also proved the value of speed in 1704 when he boldly marched an army of 21,000 Dutch and English troops on a 250-mile march across Europe in just five weeks to place themselves between French and Bavarian forces and their target of Vienna. Had Vienna been attacked, it would have forced England’s ally the Holy Roman Empire out of the conflict, giving France the victory in the War of the Spanish Succession. This march was made all the more challenging as Marlborough had to find a way to feed and equip his army along this march without unnecessarily burdening the neutral and friendly territories they were marching through.

Marlborough’s maneuver threw the Bavarian and French forces off-balance. What originally was supposed to be an “easy” French victory culminated in a crushing defeat for the French at Blenheim which turned the momentum of the war. This victory solidified Marlborough’s reputation and even resulted in the British government agreeing to build a lavish palace (called Blenheim Palace in honor of the battle) as a reward to Marlborough.

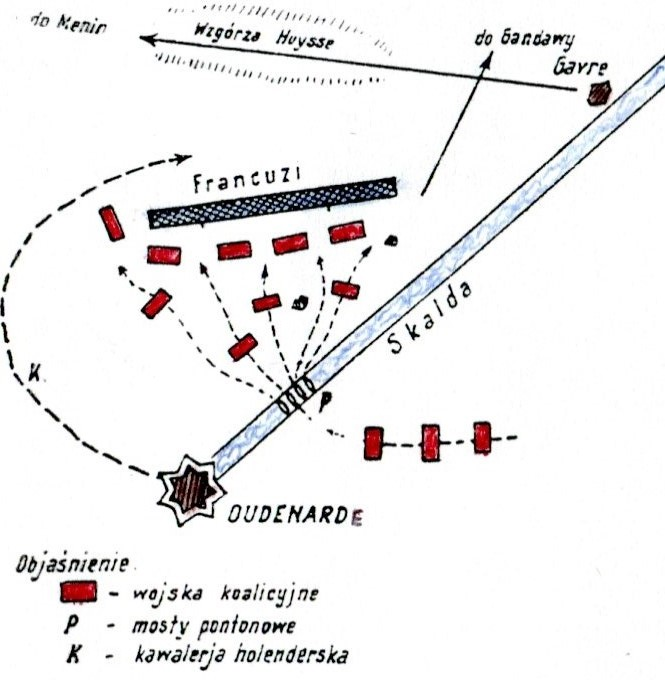

Marlborough proved the importance of speed again at the Battle of Oudenarde. In 1708, French forces captured Ghent and Bruges (in modern day Belgium), threatening the alliance’s ability to maintain contact with Britain. Recognizing this, Marlborough force-marched his army to the city of Oudenarde, marching 30 miles in about as many hours. The French, confident from their recent victories and suffering from an internal leadership squabble, misjudged the situation, allowing Marlborough’s forces to build five pontoon bridges to move his 80,000 soldiers across the nearby river.

When the French commander received news that the allies were already at Oudenarde building bridges, he said, “If they are there, then the devil must have carried them. Such marching is impossible!“

Marlborough’s forces, not yet at full strength, engaged the French, buying sufficient time for his forces to cross and form up. Once in formation, they counterattacked and collapsed one wing of the French line, saving the Allied position in the Netherlands, and resulting in a bad defeat for French forces.

For Startups

The pivotal role speed played in achieving victory for Subutai and the Duke of Marlborough apply in the startup domain as well. The ability to make fast decisions, to quickly shift focus to rapidly adapt to a new market context creates opportunities that slower moving incumbents (and military commanders!) cannot seize. Speed also gifts resiliency against mistakes and weak positions, in much the same way that speed let the Mongols and the Anglo-Prussian-Dutch alliance overcome their initial missteps at Kalka River and Oudenarde. Founders would be wise to remember to embrace speed of action in all they do.

Facebook and it’s (now in)famous “move fast, break things” motto is one classic example of how a company can internalize speed as a culture. It leveraged that to ship products and features which has kept it a leader in social and AI even in the face of constant competition and threats from well-funded companies like Google, Snapchat, and Bytedance.

Principle 4: Unconventional teams win

Another unifying hallmark of the great commanders is that they made unconventional choices with regards to their army composition. Relative to their peers, these commanders tended to build armies that were more diverse in class and nationality. While this required exceptional communication and inspiration skills, it gave the commanders significant advantages:

- Ability to recruit in challenging conditions: For many of the commanders, the unconventional team structure was a necessity to build up the forces they needed given logistical / resource constraints while operating in enemy territory.

- Operational flexibility from new tactics: Bringing on personnel from different backgrounds let commanders incorporate additional tactics and strategies, creating a more effective and flexible fighting force.

The Carthaginian general Hannibal Barca for example famously fielded a multi-nationality army consisting of Carthaginians, Libyans, Iberians, Numidians, Balearic soldiers, Gauls, and Italians. This allowed Hannibal to raise an army in hostile territory — after all, waging war in the heart of Italy against Rome made it difficult to get reinforcements from Carthage.

But, it also gave Hannibal’s army flexibility in tactics. Balearic slingers provided superior long range attack to the best Roman-used bows of the time. Numidian light cavalry provided Hannibal with fast reconnaissance and a quick way to flank and outmaneuver Roman forces. Gallic and Iberian soldiers provided shock infantry and cavalry. Each of these groups of soldiers added their own distinctive capabilities to Hannibal’s armies and great victories over Rome.

The Central Asian conqueror Timur similarly fielded a diverse army which included Mongols, Turks, Persians, Indians, Arabs, and others. This allowed Timur to field larger armies for his campaigns by recruiting from the countries he forced into submission. Like with Hannibal, it also gave Timur’s army access to a diverse set of tactics: war elephants (from India), infantry and siege technology from the Persians, gunpowder from the Ottomans, and more. This combination of operational flexibility and ability to field large armies let Timur build an empire which defeated every major power in Central Asia and the Middle East.

Image credit: Wikimedia

It should not be a surprise that some of the great commanders were drawn towards assembling unconventional teams as several of them were ultimately “commoners”. Subutai (a son of a blacksmith who Genghis Khan took interest in), Timur (a common thief), and Han Xin (韓信, who famously had to beg for food in his childhood) all came from relatively humble origins. Napoleon, famous for declaring the military “la carrier est ouvérte aux talents” (“the career open to the talents”) and creating the first modern order of merit Légion d’honneur (open to all, regardless of social class), was similarly motivated by the difficulties he faced in securing promotion early in his career due to his not being from the French nobility.

But, by embracing more of a meritocracy, Napoleon was ultimately able to field some of the largest European armies in existence as he waged war successfully against every other major European power (at once).

Image Credit: Wikimedia

For Startups

Hiring is one of the key tasks for startup founders. While hiring the people that larger, better-resourced companies want to can be helpful for a startup, it’s important to always remember that transformative victories require unconventional approaches. Leaning on unconventional hires may help you get out of a salary bidding war with those deeper-pocketed competitors. Choosing unconventional hires may also add different skills and perspectives to the team.

In pursuing this strategy, it’s also vital to excel at communication & organization as well as fostering a shared sense of purpose. All teams require strong leadership to be effective but this is especially true with an unconventional team composition facing uphill odds.

The enterprise API company Zapier is one example of taking an unconventional approach to team construction by having been 100% remote from inception (pre-COVID even). This let the company assemble a team without being confined by location and eliminate the need to spend on unnecessary facilities. They’ve had to invest in norms around documentation and communication to make this work, and, while it’d be too far of a leap to argue all startups should go 100% remote, for Zapier’s market and team culture, it’s worked.

Principle 5: Pick bold, decisive battles

When in a challenging environment with limited resources, it’s important to prioritize decisive moves — actions which can result in a huge payoff — even if risky over safer, less impactful ones. This is as true for startups, which have limited runway and need to make a big splash in order to fundraise, as for military commanders who need more than just battlefield wins but strategic victories.

Few understood this as well as the Carthaginian general Hannibal Barca who, in waging the Second Punic War against Rome, crossed the Alps from Spain with his army in 218 BCE (at the age of 29!). Memorialized in many works of art (see below for one by Francisco Goya), this was a dangerous move (one that resulted in the loss of many men and almost his entire troop of war elephants) and was widely considered to be impossible.

While history (rightly) remembers Hannibal’s boldness, it’s important to remember that Hannibal’s move was highly calculated. He realized that the Gauls in Northern Italy, who had recently been subjugated by the Romans, were likely to welcome a Roman rival. Through his spies, he also knew that Rome was planning an invasion of Carthage in North Africa. He knew he had little chance to bypass the Roman navy or Roman defensive placements if he invaded in another way.

And Hannibal’s bet paid off! Having caught the Romans entirely by surprise, they cancelled their planned invasion of Africa, and Hannibal lined up many Gallic allies to his cause. Within two years of his entry into Italy, Hannibal trounced the Roman armies sent to battle him at the River Ticinus, at the River Trebia, and at Lake Trasimene. Shocked by their losses, the Romans elected two consuls with the mandate to battle Hannibal and stop him once and for all.

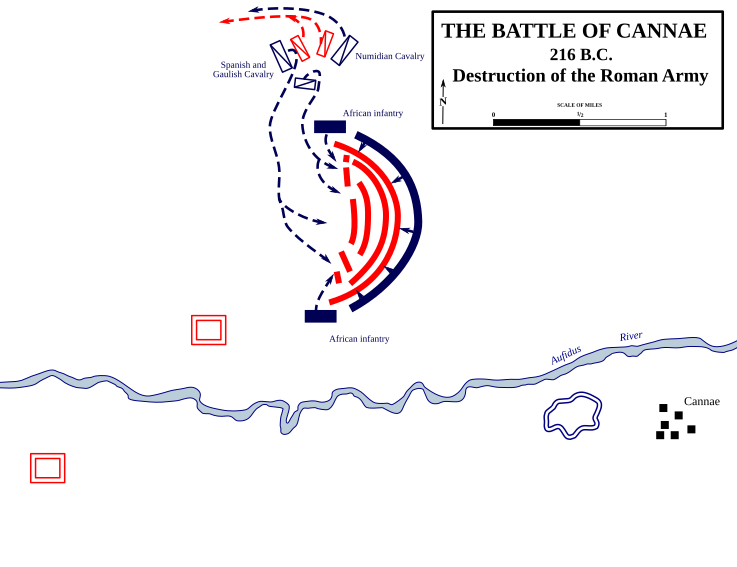

Knowing this, Hannibal seized a supply depot at the town of Cannae, presenting a tempting target to the Roman consuls to prove themselves. They (foolishly) took the bait. Despite fielding over 80,000 soldiers against Hannibal’s 50,000, Hannibal successfully executed a legendary double-envelopment maneuver (see below) and slaughtered almost the entire Roman force that met him in battle.

Image Credit: Wikimedia

To put this into perspective, in the 2 years after Hannibal crossed the Alps, Hannibal’s army killed 20% of all male Romans over the age of 17 (including at least 80 Roman Senators and one previous consul). Cannae is today considered one of the greatest examples of military tactical brilliance, and, as historian Will Durant wrote, “a supreme example of generalship, never bettered in history”.

Cannae was a great example of Hannibal’s ability to pick a decisive battle with favorable odds. Hannibal knew that his only chance was to encourage the city-states of Italy to side with him. He knew the Romans had just elected consuls itching for a fight. He chose the field of battle by seizing a vital supply depot at Cannae. Considering the Carthaginians had started and pulled back from several skirmishes with the Romans in the days leading up to the battle, it’s clear Hannibal also chose when to fight, knowing full well the Romans outnumbered him. After Cannae, many Italian city-states and the kingdom of Macedon sided with Carthage. That Carthage ultimately lost the Second Punic War is a testament more to Rome’s indomitable spirit and the sheer odds Hannibal faced than any indication of Hannibal’s skills.

In the Far East, about a decade later, the brilliant Chinese military commander Han Xin (韓信) was laying the groundwork for the creation of the Han Dynasty (漢朝) in a China-wide civil war known as the the Chu-Han contention between the State of Chu (楚) and the State of Han (漢) led by Liu Bang (劉邦, who would become the founding emperor Gaozu 高祖 of the Han Dynasty 漢朝).

Under the leadership of Han Xin (韓信), the State of Han (漢) won many victories over their neighbors. Overconfident from those victories, his king Liu Bang (劉邦) led a Han (漢) coalition to a catastrophic defeat when he briefly captured but then lost the Chu (楚) capital of Pengcheng (彭城) in 205 BCE. Chu forces (楚) were even able to capture the king’s father and wife as hostages, and several Han (漢) coalition states switched their loyalty to the Chu (楚).

To fix his king’s blunder, Han Xin (韓信) tasked the main Han (漢) army with setting up fortified positions in the Central Plain, drawing Chu (楚) forces there. Han Xin (韓信) would himself take a smaller force of less experienced soldiers to attack rival states in the North to rebuild the Han (漢) military position.

After successfully subjugating the State of Wei (魏), Han Xin (韓信)’s forces moved to attack the State of Zhao (趙, also called Dai 代) through the Jingxing Pass (井陘關) in late 205 BCE. The Zhao (趙) forces, which outnumbered Han Xin (韓信)’s, encamped on the plain just outside the pass to meet them.

Sensing an opportunity to deal a decisive blow to the overconfident Zhao (趙), Han Xin (韓信) ordered a cavalry unit to sneak into the mountains behind the Zhao (趙) camp and to remain hidden until battle started. He then ordered half of his remaining army to position themselves in full view of the Zhao (趙) forces with their backs to the Tao River (洮水), something Sun Tzu’s Art of War (孫子兵法) explicitly advises against (due to the inability to retreat). This “error” likely reinforced the Zhao (趙) commander’s overconfidence, as he made no move to pre-emptively flank or deny the Han (漢) forces their encampment.

Han Xin (韓信) then deployed his full army which lured the Zhao (趙) forces out of their camp to counterattack. Because the Tao River (洮水) cut off all avenues of escape, the outnumbered Han (漢) forces had no choice but to dig in and fight for their lives, just barely holding the Zhao (趙) forces at bay. By luring the enemy out for what appeared to be “an easy victory”, Han Xin (韓信) created an opportunity for his hidden cavalry unit to capture the enemy Zhao (趙) camp, replacing their banners with those of the Han (漢). The Zhao (趙) army saw this when they regrouped, which resulted in widespread panic as the Zhao (趙) army concluded they must be surrounded by a superior force. The opposition’s morale in shambles, Han Xin (韓信) ordered a counter-attack and the Zhao (趙) army crumbled, resulting in the deaths of the Zhao (趙) commander and king!

Han Xin (韓信) bet his entire outnumbered command on a deception tactic based on little more than an understanding of his army’s and the enemy’s psychology. He won a decisive victory which helped reverse the tide of the war. The State of Zhao (趙) fell, and the State of Jiujiang (九江) and the State of Yan (燕) switched allegiances to the Han (漢). This battle even inspired a Chinese expression “fighting a battle with one’s back facing a river” (背水一戰) to describe fighting for survival in a “last stand”.

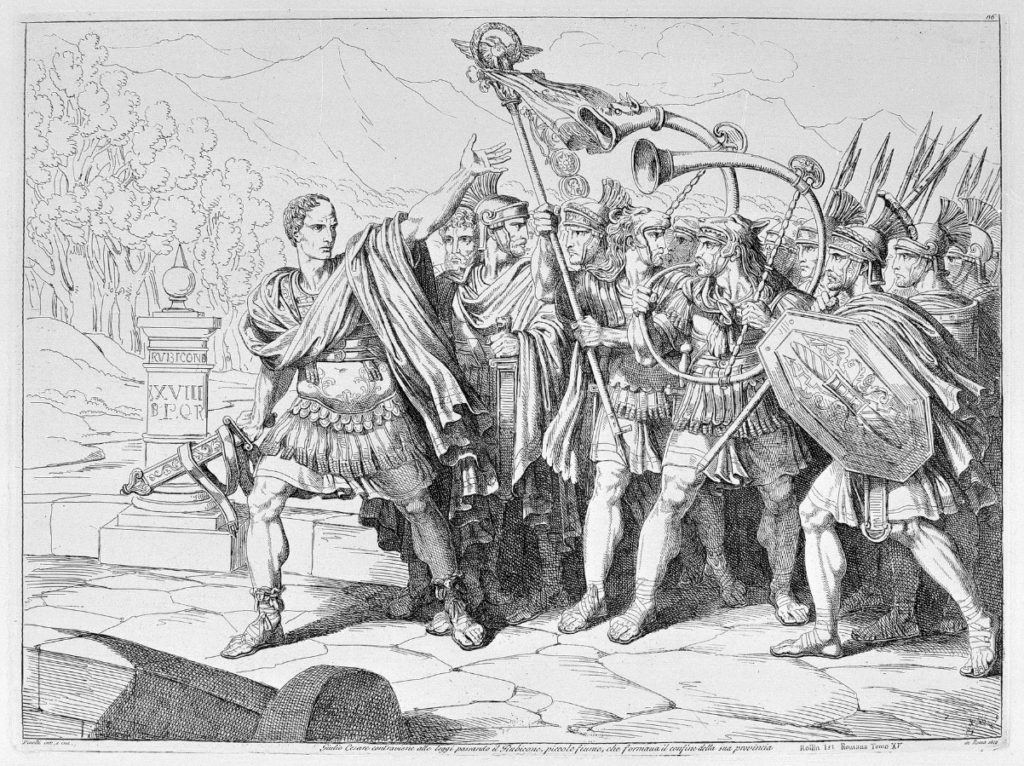

Roughly a century later, on the other side of the world, the Roman statesman and military commander Julius Caesar made a career of turning bold, decisive bets into personal glory. After Caesar conquered Gaul, Caesar’s political rivals led by Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great), a famed military commander, demanded Caesar return to Rome and give up his command. Caesar refused and crossed the Rubicon, a river marking the boundary of Italy, in January 49 BCE starting a Roman Civil War and coining at least two famous expressions (including alea iacta est – “the die is cast”) for “the point of no return”.

This bold move came as a complete shock to the Roman elite. Pompey and his supporters fled Rome. Taking advantage of this, Caesar captured Italy without much bloodshed. Caesar then pursued Pompey to Macedon, seeking a decisive land battle which Pompey, wisely, given his broad network of allies and command of the Roman navy, refused to give him. Instead, Caesar tried and failed to besiege Pompey at Dyrrhachium which forced him into retreat in Greece.

Pompey’s supporters, however, lacked Pompey’s patience (and judgement). Overconfident from their naval strength, numerical advantage, and Caesar’s failure at Dyrrhachium, they pressured Pompey into a battle with Caesar who was elated at the opportunity. In the summer of 48 BCE, the two sides met at the Battle of Pharsalus.

Always cautious, Pompey took up a position on a mountain and oriented his forces such that his larger cavalry wing would have ability to overpower Caesar’s cavalry and then flank Caesar’s forces while his numerically superior infantry would be arranged deeper to smash through or at least hold back Caesar’s lines.

Caesar made a bold tactical choice when he saw Pompey’s formation. He thinned his (already outnumbered) lines to create a 4th reserve line of veterans which he positioned behind his cavalry at an angle (see battle formation above).

Caesar initiated the battle and attacked with two of his infantry lines. As Caesar expected, Pompey ordered a cavalry charge which soon forced back Caesar’s outnumbered cavalry. But Pompey’s cavalry then encountered Caesar’s 4th reserve line which had been instructed to use their javelins to stab at the faces of Pompey’s cavalry like bayonets. Pompey’s cavalry, while larger in size, was made up of relatively inexperienced soldiers and the shock of the attack caused them to panic. This let Caesar’s cavalry regroup and, with the 4th reserve line, swung around Pompey’s army completing an expert flanking maneuver. Pompey’s army, now surrounded, collapsed once Caesar sent his final reserve line into battle.

Caesar’s boldness and speed of action let him take advantage of a lapse in Pompey’s judgement. Seeing a rare opportunity to win a decisive battle, Caesar was even willing to risk a disadvantage in infantry, cavalry, and position (Pompey’s army had the high ground and had forced Caesar to march to him). But this strategic and tactical gamble (thinning his lines to counter Pompey’s cavalry charge) paid off as Pharsalus shattered the myth of Pompey’s inevitability. Afterwards, Pompey’s remaining allies fled or defected to Caesar, and Pompey himself fled to Egypt where he was assassinated (by a government wishing to win favor with Caesar). And, all of this — from Gaul to crossing the Rubicon to the Civil War — paved the way for Caesar to become the undisputed master of Rome.

For Startups

Founders need to take bold, oftentimes uncomfortable bets that have large payoffs. While a large company can take its time winning a war of attrition, startups need to score decisive wins quickly in order to attract talent, win deals, and shift markets towards them. Only taking the “safe and rational” path is a failure to recognize the opportunity cost when operating with limited resources.

In other words, founders need to find their own Alps / Rubicons to cross.

In the startup world, few moves are as bold (while also uncomfortable and risky) as big pivots. But, there are examples of incredible successes like Slack that were able to make this work. In Slack’s case, the game they originally developed ended up a flop, but CEO & founder Stewart Butterfield felt the messaging product they had built to support the game development had potential. Leaning on that insight, over the skepticism of much of his team and some high profile investors, Butterfield made a bet-the-company move similar to Han Xin (韓信) digging in with no retreat which created a seminal product in the enterprise software space.

Summary

I hope I’ve been able to show that history’s greatest military commanders can offer valuable lessons on leadership and strategy for startup founders.

The five principles derived from studying some of the commanders’ campaigns – the importance of getting in the trenches, achieving tactical superiority, moving fast, building unconventional teams, and picking bold, decisive battles – played a key role in the commanders’ success and generalize well to startup execution.

After all, what is a more successful founder than one who can recruit teams despite resource constraints (unconventional teams), inspire them (by getting in the trenches alongside them), and move with speed & urgency (move fast) to take a competitive edge (achieve tactical superiority) and apply it where there is the greatest chance of a huge impact on the market (pick bold, decisive battles).