I’m oftentimes asked what determines the prices that companies get bought for: after all, why does one app company get bought for $19 billion and a similar app get bought at a discount to the amount of investor capital that was raised?

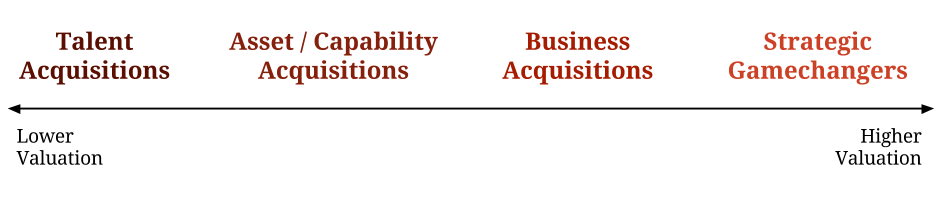

While specific transaction values depend a lot on the specific acquirer (i.e. how much cash on hand they have, how big they are, etc.), I’m going to share a framework that has been very helpful to me in thinking about acquisition valuations and how startups can position themselves to get more attractive offers. The key is understanding that, all things being equal, why you’re being acquired determines the buyer’s willingness to pay. These motivations fall on a spectrum dividing acquisitions into four types:

- Talent Acquisitions: These are commonly referred to in the tech press as “acquihires”. In these acquisitions, the buyer has determined that it makes more sense to buy a team than to spend the money, time, and effort needed to recruit a comparable one. In these acquisitions, the size and caliber of the team determine the purchase price.

- Asset / Capability Acquisitions: In these acquisitions, the buyer is in need of a particular asset or capability of the target: it could be a portfolio of patents, a particular customer relationship, a particular facility, or even a particular product or technology that helps complete the buyer’s product portfolio. In these acquisitions, the uniqueness and potential business value of the assets determine the purchase price.

- Business Acquisitions: These are acquisitions where the buyer values the target for the success of its business and for the possible synergies that could come about from merging the two. In these acquisitions, the financials of the target (revenues, profitability, growth rate) as well as the benefits that the investment bankers and buyer’s corporate development teams estimate from combining the two businesses (cost savings, ability to easily cross-sell, new business won because of a more complete offering, etc) determine the purchase price.

- Strategic Gamechangers: These are acquisitions where the buyer believes the target gives them an ability to transform their business and is also a critical threat if acquired by a competitor. These tend to be acquisitions which are priced by the buyer’s full ability to pay as they represent bets on a future.

What’s useful about this framework is that it gives guidance to companies who are contemplating acquisitions as exit opportunities:

- If your company is being considered for a talent acquisition, then it is your job to convince the acquirer that you have built assets and capabilities above and beyond what your team alone is worth. Emphasize patents, communities, developer ecosystems, corporate relationships, how your product fills a distinct gap in their product portfolio, a sexy domain name, anything that might be valuable beyond just the team that has attracted their interest.

- If a company is being considered for an asset / capability acquisition, then the key is to emphasize the potential financial trajectory of the business and the synergies that can be realized after a merger. Emphasize how current revenues and contracts will grow and develop, how a combined sales and marketing effort will be more effective than the sum of the parts, and how the current businesses are complementary in a real way that impacts the bottom line, and not just as an interesting “thing” to buy.

- If a company is being evaluated as a business acquisition, then the key is to emphasize how pivotal a role it can play in defining the future of the acquirer in a way that goes beyond just what the numbers say about the business. This is what drives valuations like GM’s acquisition of Cruise (which was a leader in driverless vehicle technology) for up to $1B, or Facebook’s acquisition of WhatsApp (messenger app with over 600 million users when it was acquired, many in strategic regions for Facebook) for $19B, or Walmart’s acquisition of Jet.com (an innovator in eCommerce that Walmart needs to help in its war for retail marketshare with Amazon.com).

The framework works for two reasons: (1) companies are bought, not sold, and the price is usually determined by the party that is most willing to walk away from a deal (that’s usually the buyer) and (2) it generally reflects how most startups tend to create value over time: they start by hiring a great team, who proceed to build compelling capabilities / assets, which materialize as interesting businesses, which can represent the future direction of an industry.

Hopefully, this framework helps any tech industry onlooker wondering why acquisition valuations end up at a certain level or any startup evaluating how best to court an acquisition offer.

Thought this was interesting? Check out some of my other pieces on how VC works / thinks

Leave a Reply