Everywhere you look, the message seems clear: early detection (of cancer & disease) saves lives. Yet behind the headlines, companies developing these screening tools face a different reality. Many tests struggle to gain approval, adoption, or even financial viability. The problem isn’t that the science is bad — it’s that the math is brutal.

This piece unpacks the economic and clinical trade-offs at the heart of the early testing / disease screening business. Why do promising technologies struggle to meet cost-effectiveness thresholds, despite clear scientific advances? And what lessons can diagnostic innovators take from these challenges to improve their odds of success? By the end, you’ll have a clearer view of the challenges and opportunities in bringing new diagnostic tools to market—and why focusing on the right metrics can make all the difference.

The brutal math of diagnostics

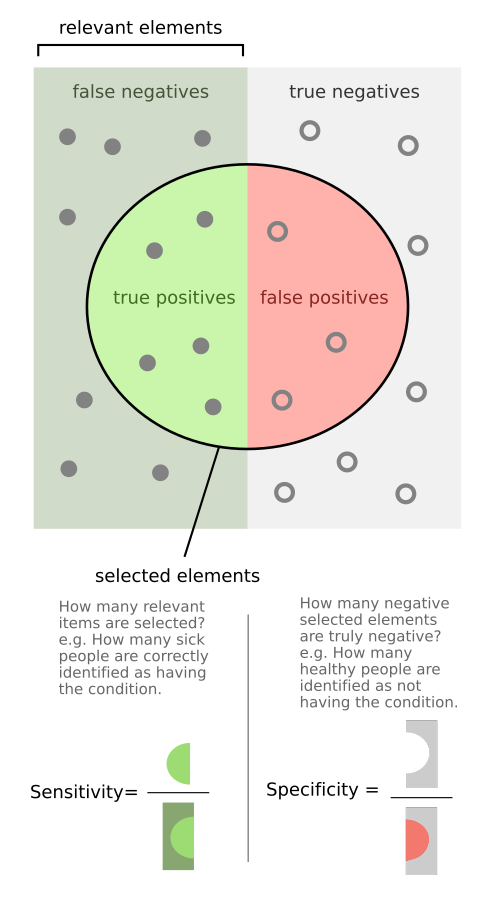

Technologists often prioritize metrics like sensitivity (also called recall) — the ability of a diagnostic test to correctly identify individuals with a condition (i.e., if the sensitivity of a test is 90%, then 90% of patients with the disease will register as positives and the remaining 10% will be false negatives) — because it’s often the key scientific challenge and aligns nicely with the idea of getting more patients earlier treatment.

But when it comes to adoption and efficiency, specificity — the ability of a diagnostic test to correctly identify healthy individuals (i.e., if the specificity of a test is 90%, then 90% of healthy patients will register as negatives and the remaining 10% will be false positives) — is usually the more important and overlooked criteria.

The reason specificity is so important is that it can have a profound impact on a test’s Positive Predictive Value (PPV) — whether or not a positive test result means a patient actually has a disease (i.e., if the positive predictive value of a test is 90%, then a patient that registers as positive has a 90% chance of having the disease and 10% chance of actually being healthy — being a false positive).

What is counter-intuitive, even to many medical and scientific experts, is that because (by definition) most patients are healthy, many high accuracy tests have disappointingly low PPV as most positive results are actually false positives.

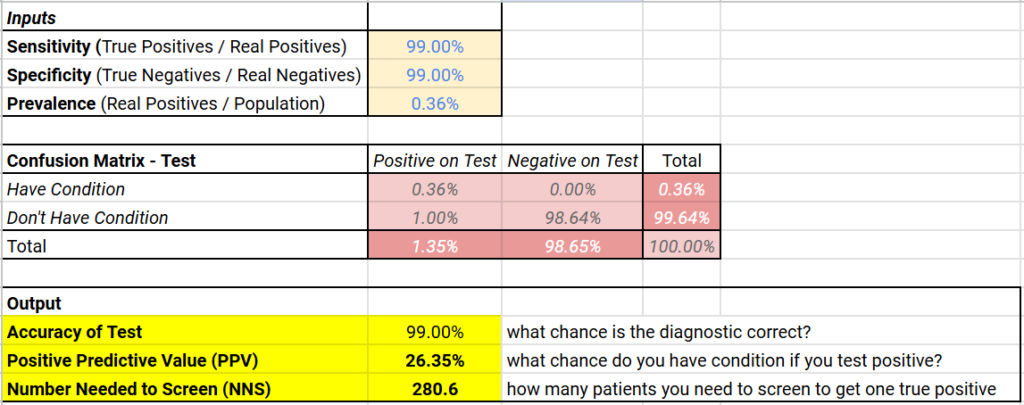

Let me present an example (see table below for summary of the math) that will hopefully explain:

- There are an estimated 1.2 million people in the US with HIV — that is roughly 0.36% (the prevalence) of the US population

- Let’s say we have an HIV test with 99% sensitivity and 99% specificity — a 99% (very) accurate test!

- If we tested 10,000 Americans at random, you would expect roughly 36 of them (0.36% x 10,000) to be HIV positive. That means, roughly 9,964 are HIV negative

- 99% sensitivity means 99% of the 36 HIV positive patients will test positive (99% x 36 = ~36)

- 99% specificity means 99% of the 9,964 HIV negative patients will test negative (99% x 9,964 = ~9,864) while 1% (1% x 9,964 = ~100) would be false positives

- This means that even though the test is 99% accurate, it only has a positive predictive value of ~26% (36 true positives out of 136 total positive results)

Below (if you’re on a browser) is an embedded calculator which will run this math for any values of disease prevalence and sensitivity / specificity (and here is a link to a Google Sheet that will do the same), but you’ll generally find that low disease rates result in low positive predictive values for even very accurate diagnostics.

Typically, introducing a new diagnostic means balancing true positives against the burden of false positives. After all, for patients, false positives will result in anxiety, invasive tests, and, sometimes, unnecessary treatments. For healthcare systems, they can be a significant economic burden as the cost of follow-up testing and overtreatment add up, complicating their willingness to embrace new tests.

Below (if you’re on a browser) is an embedded calculator which will run the basic diagnostic economics math for different values of the cost of testing and follow-up testing to calculate the cost of testing and follow-up testing per patient helped (and here is a link to a Google Sheet that will do the same)

Finally, while diagnostics businesses face many of the same development hurdles as drug developers — the need to develop cutting-edge technology, to carry out large clinical studies to prove efficacy, and to manage a complex regulatory and reimbursement landscape — unlike drug developers, diagnostic businesses face significant pricing constraints. Successful treatments can command high prices for treating a disease. But successful diagnostic tests, no matter how sophisticated, cannot, because they ultimately don’t treat diseases, they merely identify them.

Case Study: Exact Sciences and Cologuard

Let’s take Cologuard (from Exact Sciences) as an example. Cologuard is a combination genomic and immunochemistry test for colon cancer carried out on patient stool samples. It’s two primary alternatives are:

- a much less sensitive fecal immunochemistry test (FIT) — which uses antibodies to detect blood in the stool as a potential, imprecise sign of colon cancer

- colonoscopies — a procedure where a skilled physician uses an endoscope to enter and look for signs of cancer in a patient’s colon. It’s considered the “gold standard” as it functions both as diagnostic and treatment (a physician can remove or biopsy any lesion or polyp they find). But, because it’s invasive and uncomfortable for the patient, this test is typically only done every 4-10 years

Cologuard is (as of this writing) Exact Science’s primary product line, responsible for a large portion of Exact Science’s $2.5 billion in 2023 revenue. It can detect earlier stage colon cancer as well as pre-cancerous growths that could lead to cancer. Impressively, Exact Sciences also commands a gross margin greater than 70%, a high margin achieved mainly by pharmaceutical and software companies that have low per-unit costs of production. This has resulted in Exact Sciences, as of this writing, having a market cap over $11 billion.

Yet for all its success, Exact Sciences is also a cautionary note, illustrating the difficulties of building a diagnostics company.

- The company was founded in 1995, yet didn’t see meaningful revenue from selling diagnostics until 2014 (nearly 20 years later, after it received FDA approval for Cologuard)

- The company has never had a profitable year (this includes the last 10 years it’s been in-market), losing over $200 million in 2023, and in the first three quarters of 2024, it has continued to be unprofitable.

- Between 1997 (the first year we have good data from their SEC filings as summarized in this Google Sheet) and 2014 when it first achieved meaningful diagnostic revenue, Exact Sciences lost a cumulative $420 million, driven by $230 million in R&D spending, $88 million in Sales & Marketing spending, and $33 million in CAPEX. It funded those losses by issuing over $624 million in stock (diluting investors and employees)

- From 2015-2023, it has needed to raise an additional $3.5 billion in stock and convertible debt (net of paybacks) to cover its continued losses (over $3 billion from 2015-2023)

- Prior to 2014, Exact Sciences attempted to commercialize colon cancer screening technologies through partnerships with LabCorp (ColoSure and PreGenPlus). These were not very successful and led to concerns from the FDA and insurance companies. This forced Exact Sciences to invest heavily in clinical studies to win over the payers and the FDA, including a pivotal ~10,000 patient study to support Cologuard which recruited patients from over 90 sites and took over 1.5 years.

- It took Exact Sciences 3 years after FDA approval of Cologuard for its annual diagnostic revenues to exceed what it spends on sales & marketing. It continues to spend aggressively there ($727M in 2023).

While it’s difficult to know precisely what the company’s management / investors would do differently if they could do it all over again, the brutal math of diagnostics certainly played a key role.

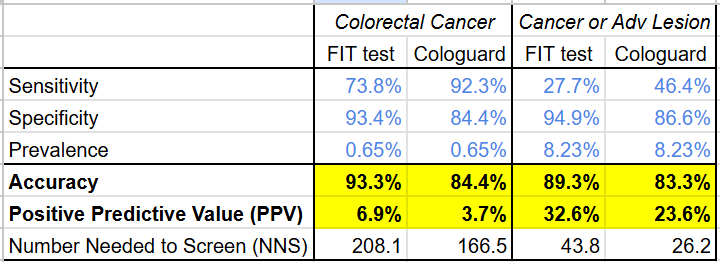

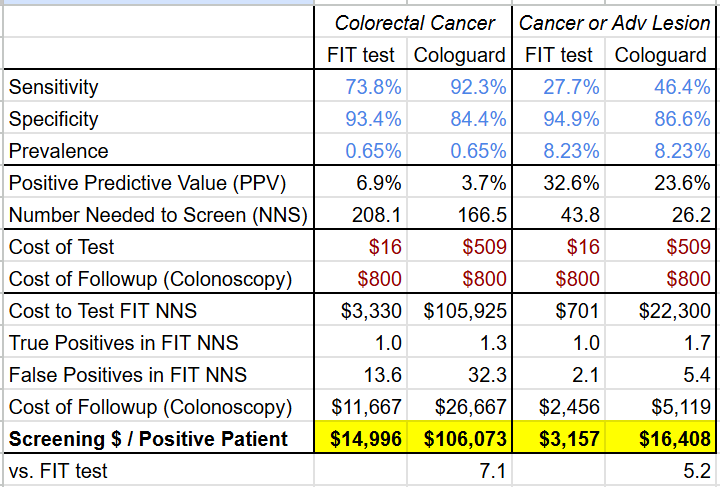

From a clinical perspective, Cologuard faces the same low positive predictive value problem all diagnostic screening tests face. From the data in their study on ~10,000 patients, it’s clear that, despite having a much higher sensitivity for cancer (92.3% vs 73.8%) and higher AUROC (94% vs 89%) than the existing FIT test, the PPV of Cologuard is only 3.7% (lower than the FIT test: 6.9%).

Even using a broader disease definition that includes the pre-cancerous advanced lesions Exact Sciences touted as a strength, the gap on PPV does not narrow (Cologuard: 23.6% vs FIT: 32.6%)

(Google Sheet link)

The economic comparison with a FIT test fares even worse due to the higher cost of Cologuard as well as the higher rate of false positives. Under the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Service’s 2024Q4 laboratory fee schedule, a FIT test costs $16 (CPT code: 82274), but Cologuard costs $509 (CPT code: 81528), over 30x higher! If each positive Cologuard and FIT test results in a follow-up colonoscopy (which has a cost of $800-1000 according to this 2015 analysis), the screening cost per cancer patient is 5.2-7.1x higher for Cologuard than for the FIT test.

(Google Sheet link)

This quick math has been confirmed in several studies.

- A study by a group at the University Medical Center of Rotterdam concluded that “Compared to nearly all other CRC screening strategies reimbursed by CMS (Medicare), [Cologuard] is less effective and considerably more costly, making it an inefficient screening option” and would only be comparable at a much lower cost (~$6-18!)

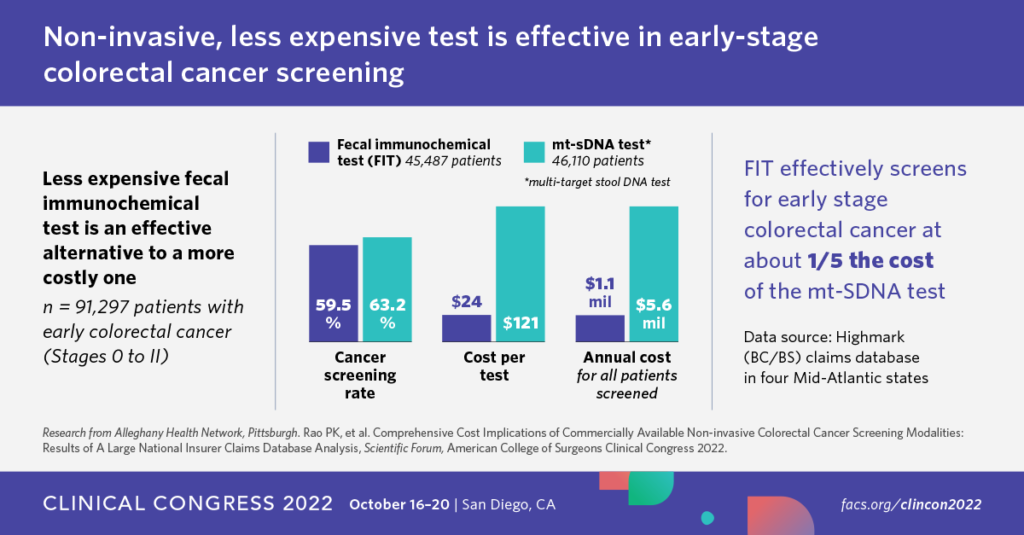

- Another study presented at the American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress in 2022 (see image below) looked at insurance reimbursement in the Alleghany Health Network and found that the FIT test was 5x cheaper in addressing early stage colon cancer.

While Medicare and the US Preventive Services Task Force concluded that the cost of Cologuard and the increase in false positives / colonoscopy complications was worth the improved early detection of colon cancer, it stayed largely silent on comparing cost-efficacy with the FIT test. It’s this unfavorable comparison that has probably required Exact Sciences to invest so heavily in sales and marketing to drive sales. That Cologuard has been so successful is a testament both to the value of being the only FDA-approved test on the market as well as Exact Science’s efforts in making Cologuard so well-known (how many other diagnostics do you know have an SNL skit dedicated to them?).

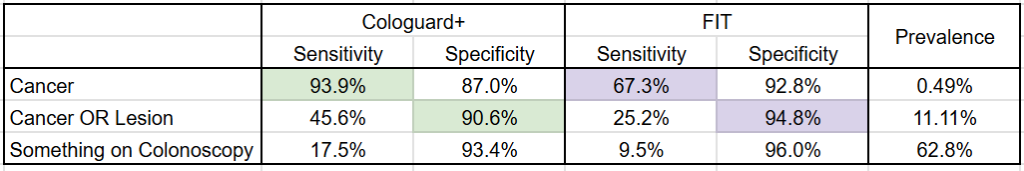

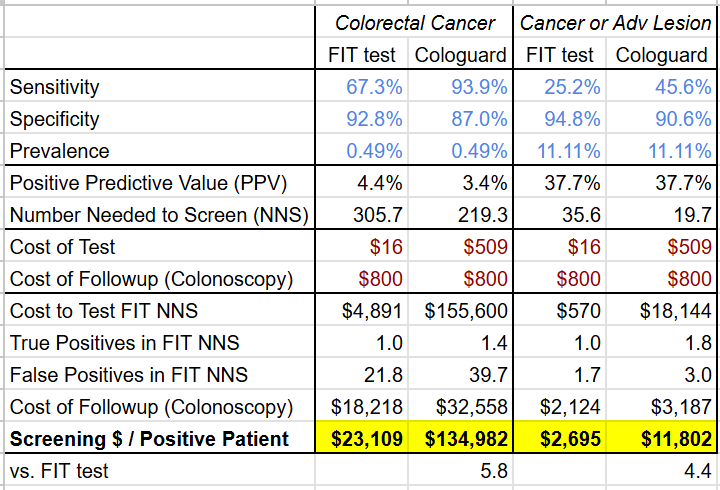

Not content to rest on the laurels of Cologuard, Exact Sciences recently published a ~20,000 patient study on their next generation colon cancer screening test: Cologuard Plus. While the study suggests Exact Sciences has improved the test across the board, the company’s marketing around Cologuard Plus having both >90% sensitivity and specificity is misleading, because the figures for sensitivity and specificity are for different conditions: sensitivity for colorectal cancer but specificity for colorectal cancer OR advanced precancerous lesion (see the table below).

(Google Sheet link)

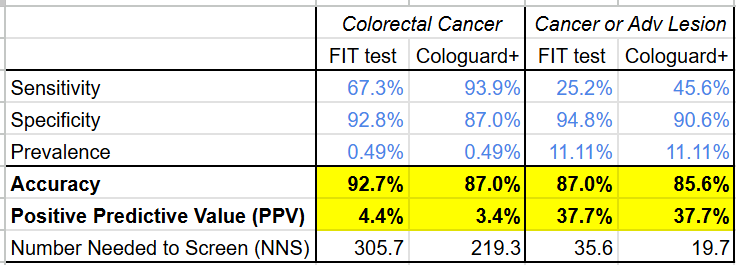

Disentangling these numbers shows that while Cologuard Plus has narrowed its PPV disadvantage (now worse by 1% on colorectal cancer and even on cancer or lesion) and its cost-efficacy disadvantage (now “only” 4.4-5.8x more expensive) vs the FIT test (see tables below), it still hasn’t closed the gap.

Time will tell if this improved test performance translates to continued sales performance for Exact Sciences, but it is telling that despite the significant time and resources that went into developing Cologuard Plus, the data suggests it’s still likely more cost effective for health systems to adopt FIT over Cologuard Plus as a means of preventing advanced colon cancer.

Lessons for diagnostics companies

The underlying math of the diagnostics business and the lessons from Exact Sciences’ long path to dramatic sales has several key lessons for diagnostic entrepreneurs:

- Focus on specificity — For diagnostic technologists, too little attention is paid to specificity while too much attention is paid on sensitivity. Positive predictive value and the cost-benefit for a health system are largely going to swing on specificity.

- Aim for higher value tests — Because the development and required validation for a diagnostic can be as high as that of a drug or medical device, it is important to pursue opportunities where the diagnostic can command a high price. These are usually markets where the alternatives are very expensive because they require new technology (e.g. advanced genetic tests) or a great deal of specialized labor (e.g. colonoscopy) or where the diagnostic directly decides on a costly course of treatment (e.g. a companion diagnostic for an oncology drug).

- Go after unmet needs — If a test is able to fill a mostly unmet need — for example, if the alternatives are extremely inaccurate or poorly adopted — then adoption will be determined by awareness (because there aren’t credible alternatives) and pricing will be determined by sensitivity (because this drives the delivery of better care). This also simplifies the sales process.

- Win beyond the test — Because performance can only ever get to 100%, each incremental point on sensitivity and specificity is both exponentially harder to achieve but also delivers less medical or financial value. As a result, it can be advantageous to focus on factors beyond the test such as regulatory approval / guidelines adoption, patient convenience, time to result, and impact on follow-up tests and procedures. Cologuard gained a great deal from being “the first FDA-approved colon cancer screening test”. Non-invasive prenatal testing, despite low positive predictive values and limited disease coverage, gained adoption in part by helping to triage follow-up amniocentesis (a procedure which has a low but still frighteningly high rate of miscarriage ~0.5%). Rapid antigen tests for COVID have also similarly been adopted despite their lower sensitivity and specificity than PCR tests due to their speed, low cost, and ability to carry out at home.

Diagnostics developers must carefully navigate the intersection of scientific innovation and financial reality, while grappling with the fact that even the most impressive technology may be insufficient without taking into account clinical and economic factors to achieve market success.

Ultimately, the path forward for diagnostic innovators lies in prioritizing specificity, targeting high-value and unmet needs, and crafting solutions that deliver value beyond the test itself. While Exact Science’s journey underscores the difficulty of these challenges, it also illustrates that with persistence, thoughtful investment, and strategic differentiation, it is possible to carve out a meaningful and impactful space in the market.

Leave a Reply