This month’s paper (from open access journal PLoS ONE) is yet again about the impact on our health of the bacteria which have decided to call our bodies home. But, instead of the bacteria living in our gut, this month is about the bacteria which live on our skin.

It’s been known that the bacteria that live on our skin help give us our particular odors. So, the researchers wondered if the mosquitos responsible for passing malaria (Anopheles) were more or less drawn to different individuals based on the scent that our skin-borne bacteria impart upon us (also, for the record, before you freak out about bacteria on your skin, remember that like the bacteria in your gut, the bacteria on your skin are natural and play a key role in maintaining the health of your skin).

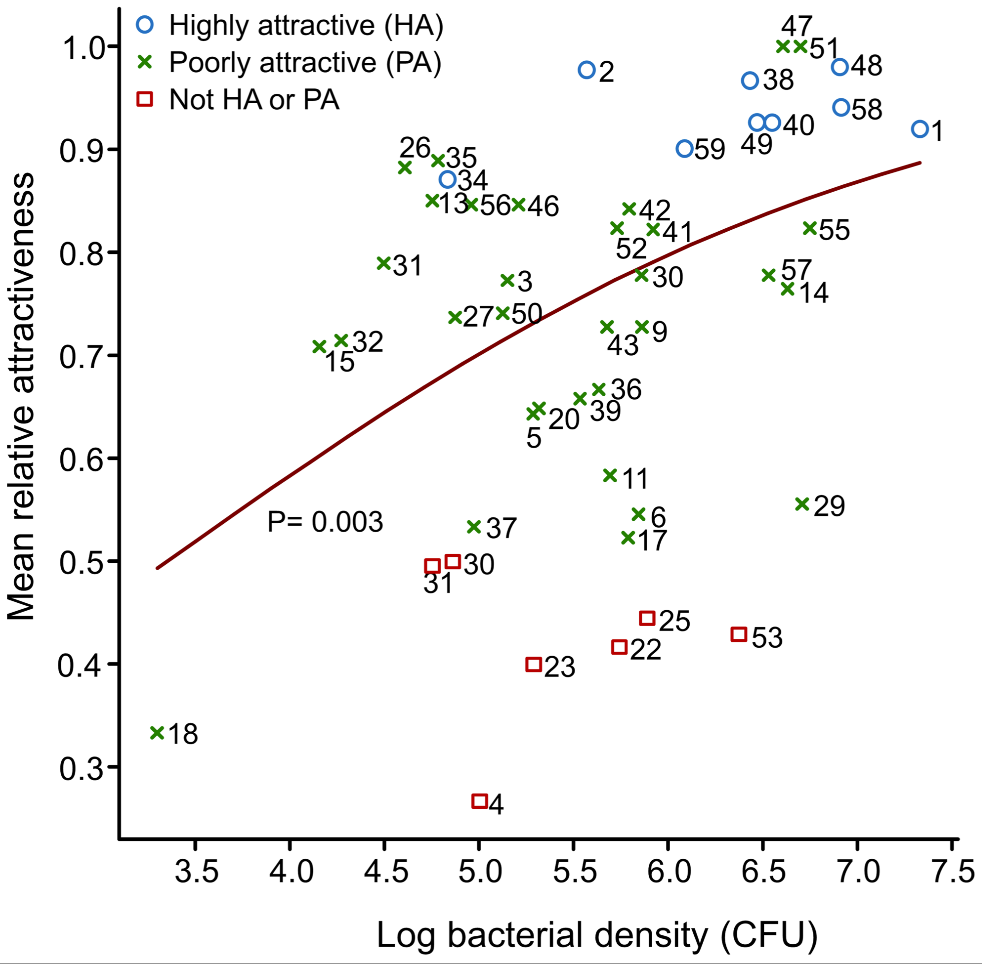

Looking at 48 individuals, they noticed a huge variation in terms of attractiveness to Anopheles mosquitos (measured by seeing how much mosquitos prefer to fly towards a chamber with a particular individual’s skin extract versus a control) which they were able to trace to two things. The first is the amount of bacteria on your skin. As shown in Figure 2 below, is that the more bacteria that you have on your skin (the higher your “log bacterial density”), the more attractive you seem to be to mosquitos (the higher your mean relative attractiveness).

The second thing they noticed was that the type of bacteria also seemed to be correlated with attractiveness to mosquitos. Using DNA sequencing technology, they were able to get a mini-census of what sort of bacteria were present on the skins of the different patients. Sadly, they didn’t show any pretty figures for the analysis they conducted on two common types of bacteria (Staphylococcus and Pseudomonas), but, to quote from the paper:

The abundance of Staphylococcus spp. was 2.62 times higher in the HA [Highly Attractive to mosquitoes] group than in the PA [Poorly Attractive to mosquitoes] group and the abundance of Pseudomonas spp. 3.11 times higher in the PA group than in the HA group.

Using further genetic analyses, they were also able to show a number of other types of bacteria that were correlated with one or the other.

So, what did I think? While I think there’s a lot of interesting data here, I think the story could’ve been tighter. First and foremost, for obvious reasons, correlation does not mean causation. This was not a true controlled experiment – we don’t know for a fact if more/specific types of bacteria cause mosquitos to be drawn to them or if there’s something else that explains both the amount/type of bacteria and the attractiveness of an individual’s skin scent to a mosquito. Secondly, Figure 2 leaves much to be desired in terms of establishing a strong trendline. Yes, if I squint (and ignore their very leading trendline) I can see a positive correlation – but truth be told, the scatterplot looks like a giant mess, especially if you include the red squares that go with “Not HA or PA”. For a future study, I think it’d be great if they could get around this to show stronger causation with direct experimentation (i.e. extracting the odorants from Staphylococcus and/or Pseudomonas and adding them to a “clean” skin sample, etc)

With that said, I have to applaud the researchers for tackling a fascinating topic by taking a very different angle. Coverage of malaria is usually focused on how to directly kill or impede the parasite (Plasmodium falciparums). This is the first treatment of the “ecology” of malaria – specifically the ecology of the bacteria on your skin! While the authors don’t promise a “cure for malaria”, you can tell they are excited about what they’ve found and the potential to find ways other than killing parasites/mosquitos to help deal with malaria, and I look forward to seeing the other ways that our skin bacteria impact our lives.

Paper: Verhulst et al. “Composition of Human Skin Microbiota Affects Attractiveness to Malaria Mosquitoes.” PLoS ONE 6(12). 17 Nov 2011. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028991