Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act has been rightfully called “the twenty-six words that created the Internet.” It is a valuable legal shield which allows internet hosts and platforms the ability to distribute user-generated content and practice moderation without unreasonable fear of being sued, something which forms the basis of all social media, user review, and user forum, and internet hosting services.

In recent months, as big tech companies have drawn greater scrutiny for the role they play in shaping our discussions, Section 230 has become a scapegoat for many of the ills of technology. Until 2021, much of that criticism has come from the Republican Party who argue incorrectly that it promotes bias on platforms with President Trump even vetoing unrelated defense legislation because it did not repeal Section 230.

So, it’s refreshing (and distressing) to see the Democrats now take their turn in misunderstanding what Section 230 does for the internet. This critique is based mainly on Senator Mark Warner’s proposed changes to Section 230 and the FAQ his office posted about the SAFE TECH act he (alongside Senators Hirono and Klobuchar) is proposing but apply to many commentators from the Democratic Party and the press which seems to have misunderstood the practical implications and have received this positively.

While I think it’s reasonable to modify Section 230 to obligate platforms to help victims of clearly heinous acts like cyberstalking, swatting, violent threats, and human rights violations, what the Democratic Senators are proposing goes far beyond that in several dangerous ways.

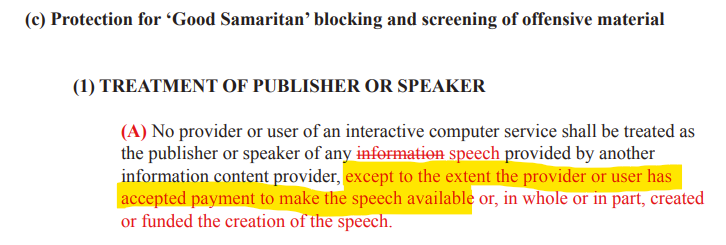

First, Warner and his colleagues have proposed carving out from Section 230 all content which accompanies payment (see below). While I sympathize with what I believe was the intention (to put a different bar on advertisements), this is remarkably short-sighted, because Section 230 applies to far more than companies with ad / content moderation policies Democrats dislike such as Facebook, Google, and Twitter.

It also encompasses email providers, web hosts, user generated review sites, and more. Any service that currently receives payment (for example: a paid blog hosting service, any eCommerce vendor who lets users post reviews, a premium forum, etc) could be made liable for any user posted content. This would make it legally and financially untenable to host any potentially controversial content.

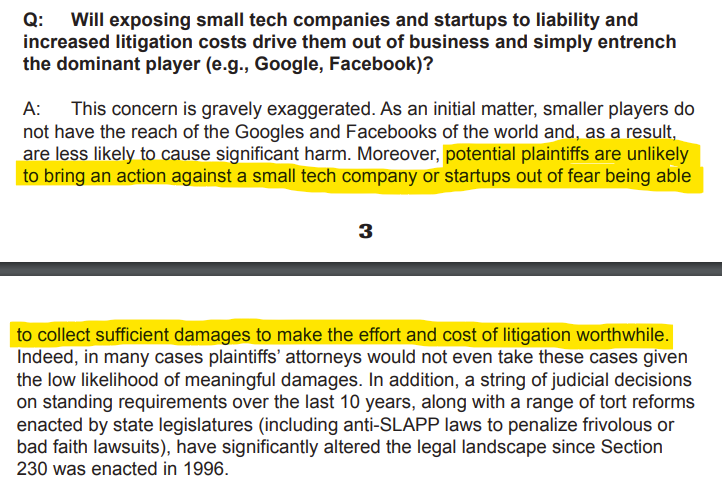

Secondly, these rules will disproportionately impact smaller companies and startups. This is because these smaller companies lack the resources that larger companies have to deal with the new legal burdens and moderation challenges that such a change to Section 230 would call for. It’s hard to know if Senator Warner’s glip answer in his FAQ that people don’t litigate small companies (see below) is ignorance or a willful desire to mislead, but ask tech startups how they feel about patent trolls and whether or not being small protects them from frivolous lawsuits

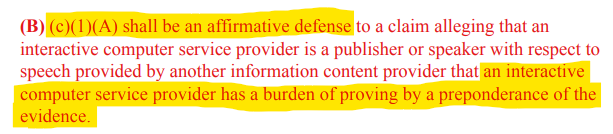

Third, the use of the language “affirmative defense” and “injunctive relief” may have far-reaching consequences that go beyond minor changes in legalese (see below). By reducing Section 230 from an immunity to an affirmative defense, it means that companies hosting content will cease to be able to dismiss cases that clearly fall within Section 230 because they now have a “burden of [proof] by a preponderance of the evidence.”

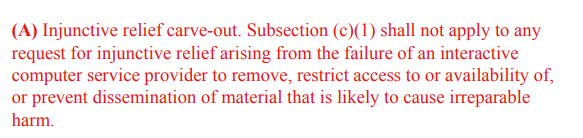

Similarly, carving out “injunctive relief” from Section 230 protections (see below) means that Section 230 doesn’t apply if the party suing is only interested in taking something down (but not financial damages)

I suspect the intention of these clauses is to make it harder for large tech companies to dodge legitimate concerns, but what this practically means is that anyone who has the money to pursue legal action can simply tie up any internet company or platform hosting content that they don’t like.

That may seem like hyperbole, but this is what happened in the UK until 2014 where libel / slander laws making it easy for wealthy individuals and corporations to sue anyone for negative press due to weak protections. Imagine Jeffrey Epstein being able to sue any platform for carrying posts or links to stories about his actions or any individual for forwarding an unflattering email about him.

There is no doubt that we need new tools and incentives (both positive and negative) to tamp down on online harms like cyberbullying and cyberstalking, and that we need to come up with new and fair standards for dealing with “fake news”. But, it is distressing that elected officials will react by proposing far-reaching changes that show a lack of thoughtfulness as it pertains to how the internet works and the positives of existing rules and regulations.

It is my hope that this was only an early draft that will go through many rounds of revisions with people with real technology policy and technology industry expertise.