The paper I will talk about this month is from April of this year and highlights the diversity of our “gut flora” (a pleasant way to describe the many bacteria which live in our digestive tract and help us digest the food we eat). Specifically, this paper highlights how a particular bacteria in the digestive tracts of some Japanese individuals has picked up a unique ability to digest certain certain sugars which are common in marine plants (e.g., Porphyra, the seaweed used to make sushi) but not in terrestrial plants.

Interestingly, the researchers weren’t originally focused on how gut flora function at all, but in understanding how marine bacteria digested marine plants. They started by studying a particular marine bacteria, Zobellia galactanivorans which was known for its ability to digest certain types of algae. Scanning the genome of Zobellia, the researchers were able to identify a few genes which were similar enough to known sugar-digesting enzymes but didn’t seem to have the ability to act on the “usual plant sugars”.

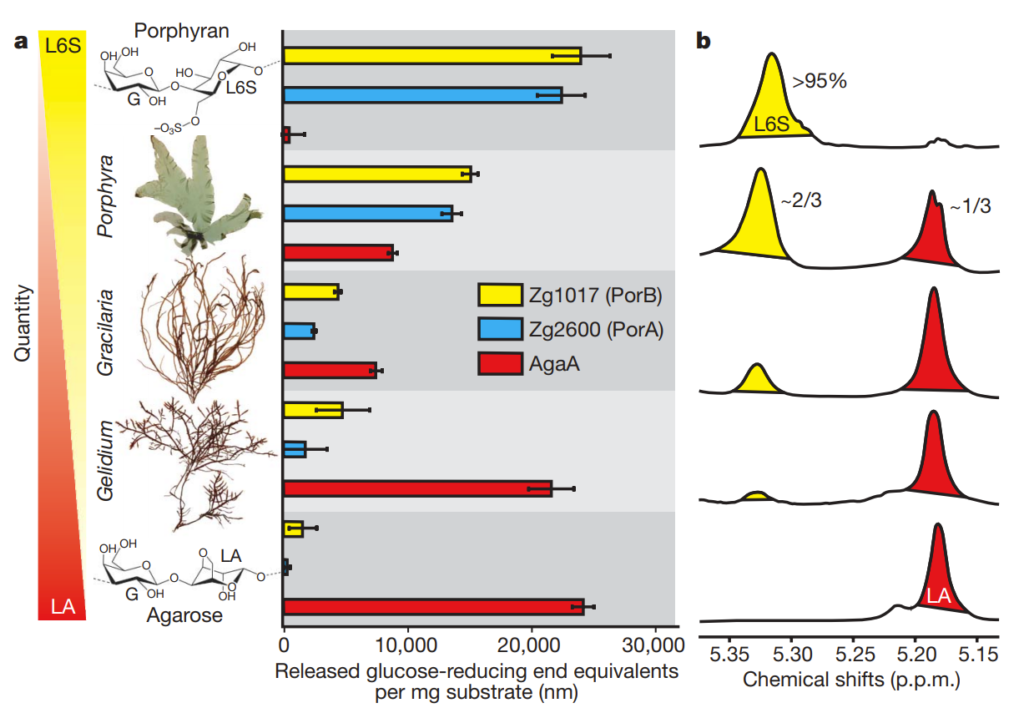

Two of the identified genes, which they called PorA and PorB, were found to be very selective in the type of plant sugar they digested. In the chart below (from Figure 1), 3 different plants are characterized along a spectrum showing if they have more LA (4-linked 3,6-anhydro-a-L-galactopyranose) chemical groups (red) or L6S (4-linked a-L-galactopyranose-6-sulphate) groups (yellow). Panel b on the right shows the H1-NMR spectrum associated with these different sugar mixes and is a chemical technique to verify what sort of sugar groups are present.

These mixes were subjected to PorA and PorB as well as AgaA (a sugar-digesting enzyme which works mainly on LA-type sugars like agarose). The bar charts in the middle show how active the respective enzymes were (as indicated by the amount of plant sugar digested).

As you can see, PorA and PorB are only effective on L6S-type sugar groups, and not LA-type sugar groups. The researchers wondered if they had discovered the key class of enzyme responsible for allowing marine life to digest marine plant sugars and scanned other genomes for other enzymes similar to PorA and PorB. What they found was very interesting

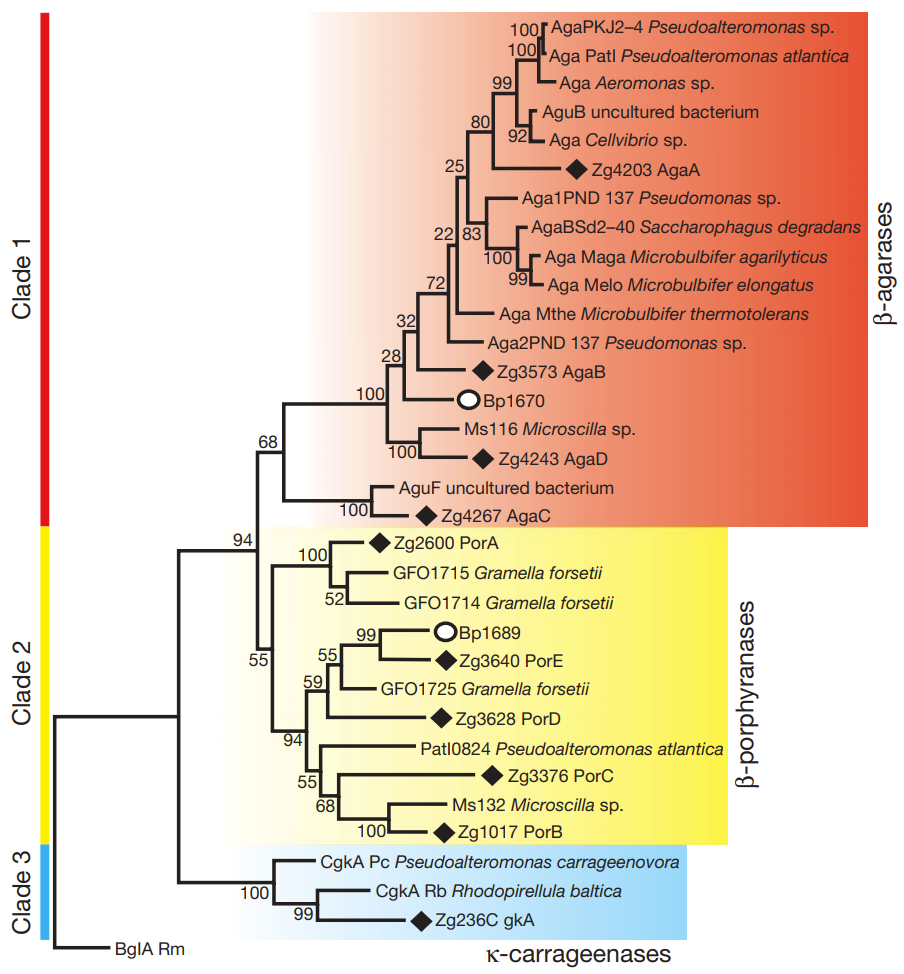

What you see above is an evolutionary family tree for PorA/PorB-like genes. The red and blue boxes represent PorA/PorB-like genes which target “usual plant sugars”, but the yellow show the enzymes which specifically target the sugars found in nori (Porphyra, hence the enzymes are called porhyranases). All the enzymes marked with solid diamonds are actually found in Z. galactanivorans (and were henced dubbed PorC, PorD, and PorE – clearly not the most imaginative naming convention). The other identified genes, however, all belonged to marine bacteria… with the notable exception of Bateroides plebeius, marked with a open circle. And Bacteroides plebeius (at least to the knowledge of the researchers at the time of this publication) has only been found in the guts of certain Japanese people!

The researchers scanned the Bacteroides plebeius genome and found that the bacteria actually had a sizable chunk of genetic material which were a much better match for marine bacteria than other similar Bacteroides strains. The researchers concluded that the best explanation for this is that the Bacteroides plebeius picked up its unique ability to digest marine plants not on its own, but from marine bacteria (in a process called Horizontal Gene Transfer or HGT), most probably from bacteria that were present on dietary seaweed. Or, to put it more simply: your gut bacteria have the ability to “steal” genes/abilities from bacteria on the food we eat!

Cool! While this is a conclusion which we can probably never truly prove (it’s an informed hypothesis based on genetic evidence), this finding does make you wonder if a similar genetic screening process could identify if our gut flora have picked up any other genes from “dietary bacteria.”

Paper: Hehemann et al, “Transfer of carbohydrate-active enzymes from marine bacteria to Japanese gut microbiota.” Nature464: 908-912 (Apr 2010) – doi:10.1038/nature08937

Leave a Reply