Despite all the speculation over why Amazon is laying off 14,000 workers, as of this writing, and with a few exceptions I’ll note below, I don’t personally worry a great deal about AI taking away jobs currently.

The reason is that while new AI agent based services and products are becoming better at replacing humans at certain tasks:

- Many tasks are not automatable — especially ones where the “product/service” is actual human interaction and judgement. And those tasks tend to be the ones that take the longest and the most people to do.

- Technological improvements can lead to increased demand. The classic examples of this are how the advent of spreadsheet software increased the number of accountants (when calculation work became cheaper and easier, the demand for accounting-style thinking to be used broadly across the business increased) or how automated teller machines (ATMs) increased the demand for human tellers (by making it imperative for convenience to have more branches).

- AI tools are great at answering questions and doing assigned tasks. But you still need a person with actual judgement and experience to ask the right questions and assign the right tasks

While the above three advantages may ultimately disappear as technology improves, in general, I am optimistic that, by making workers more productive overall, AI technology will make workers more valuable overall.

The one exception that I immediately saw, however, were entry-level knowledge workers. New (and, in most cases, young) knowledge workers (engineers, designers, analysts, writers, management consultants, etc) are uniquely not valuable when they first start a job. They lack context, judgement, and skill. They tend to only prove their value after they’ve had the chance to learn on the job. Historically, the bargain was that entry-level knowledge workers would start with relatively lower-value tasks that would, through time and exposure, help them learn the context, judgement, and skills they would need to become productive. This is, after all, the path I took as a novice management consultant and later investor.

But with new AI tools, the case for hiring these entry-level knowledge workers dramatically weakens. Claude Code might not be able to replace the judgement of a senior architect, but it can probably get up to speed on a codebase faster, write code more accurately, and all without needing rest or paid time off than a fresh-out-of-school developer. Gemini might not be able to have the same type of insights as someone with a deep rolodex in an industry, but it will certainly know more and can conduct & summarize internet research much faster than a freshly minted consultant. ChatGPT might not be able to capture the artistry or investigation skills of a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist, but it can definitely write up summaries of stock market movements or the press releases from a company better than a novice journalist.

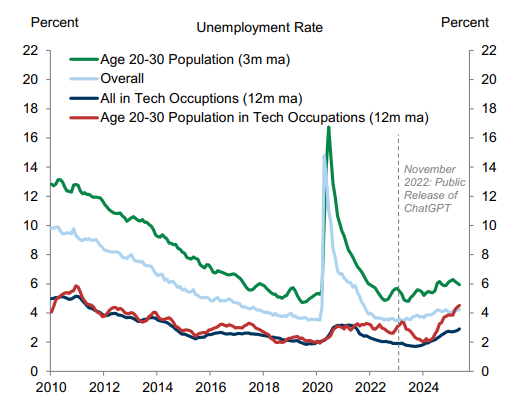

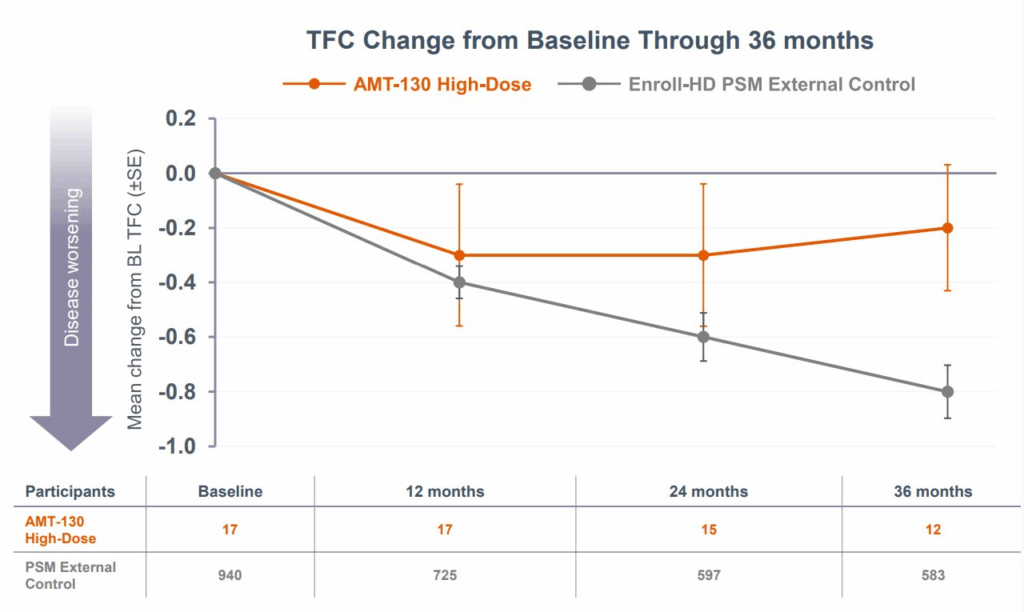

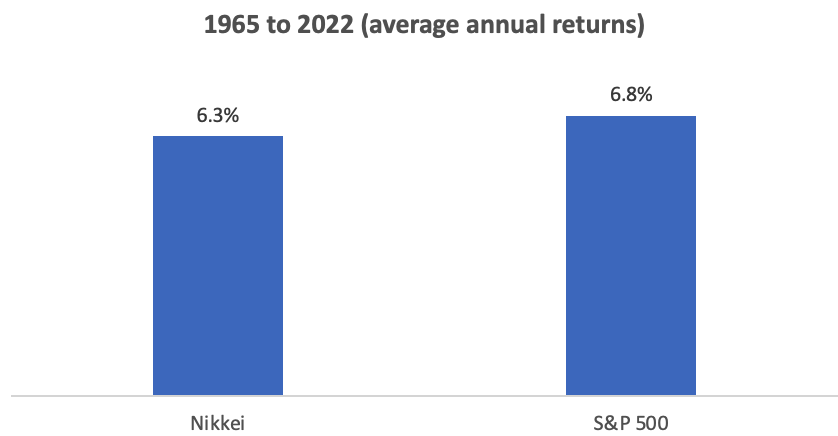

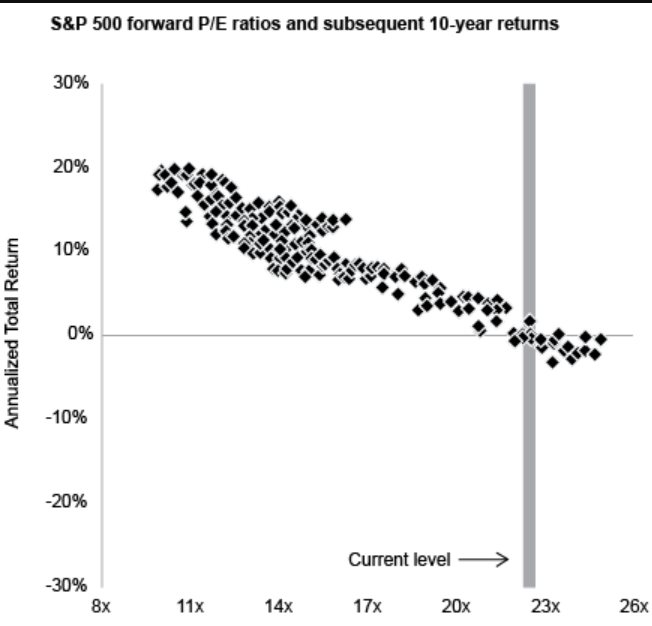

This is ultimately self-defeating — as without new junior talent, where does one find good middle-level or senior talent — but it’s also something that I fear we are already beginning to see. This Goldman Sachs research report I just read has a great Exhibit 4 showing how while new AI tools have not significantly impacted employment in general or even employment in tech, it has meaningfully increased unemployment in 20-somethings who work in tech (see image below), exactly the demographic who’s value as entry-level workers has now been largely displaced by AI.

How the tech industry (and other knowledge work professions) ultimately choose to handle this will be the defining test of how we incorporate AI into our economic lives.

Over just the last few years, AI does appear to be hurting the employment prospects of the most closely exposed workers, such as young technology workers (Exhibit 4, left). Our global economics team recently showed that employment growth has turned negative in the most AI-exposed industries, but that the aggregate labor market impact remains limited so far.