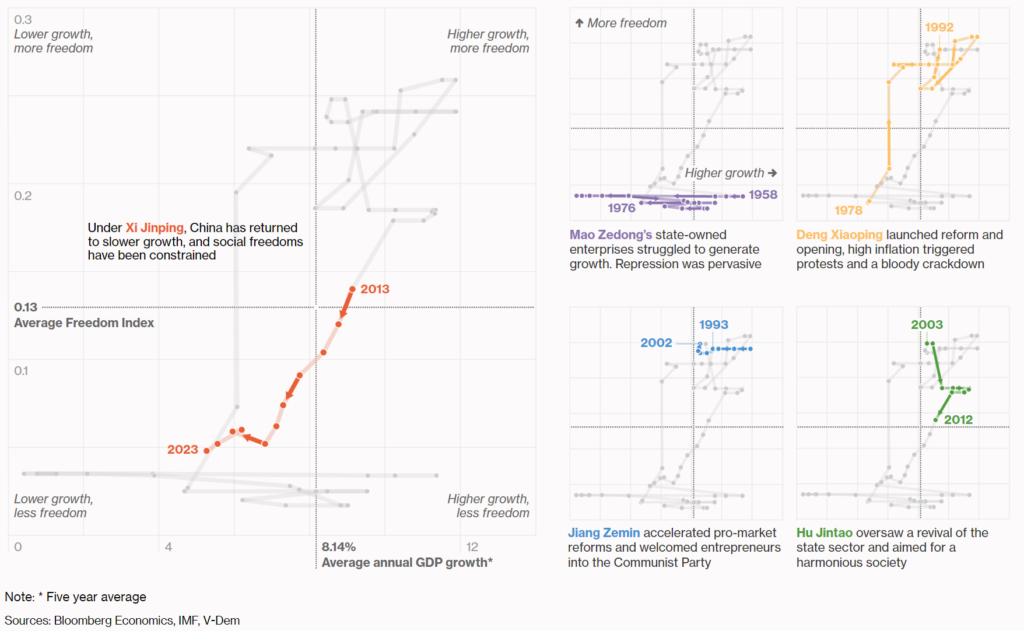

Strong regional industrial ecosystems like Silicon Valley (tech), Boston (life science), and Taiwan (semiconductors) are fascinating. Their creation is rare and requires local talent, easy access to supply chains and distribution, academic & government support, business success, and a good amount of luck.

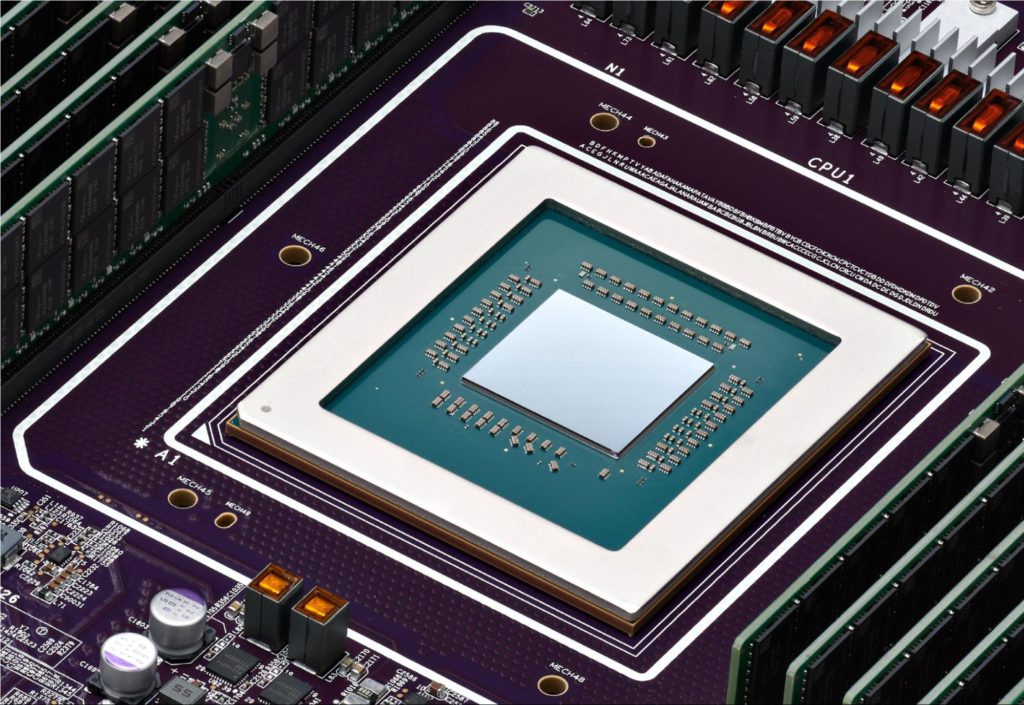

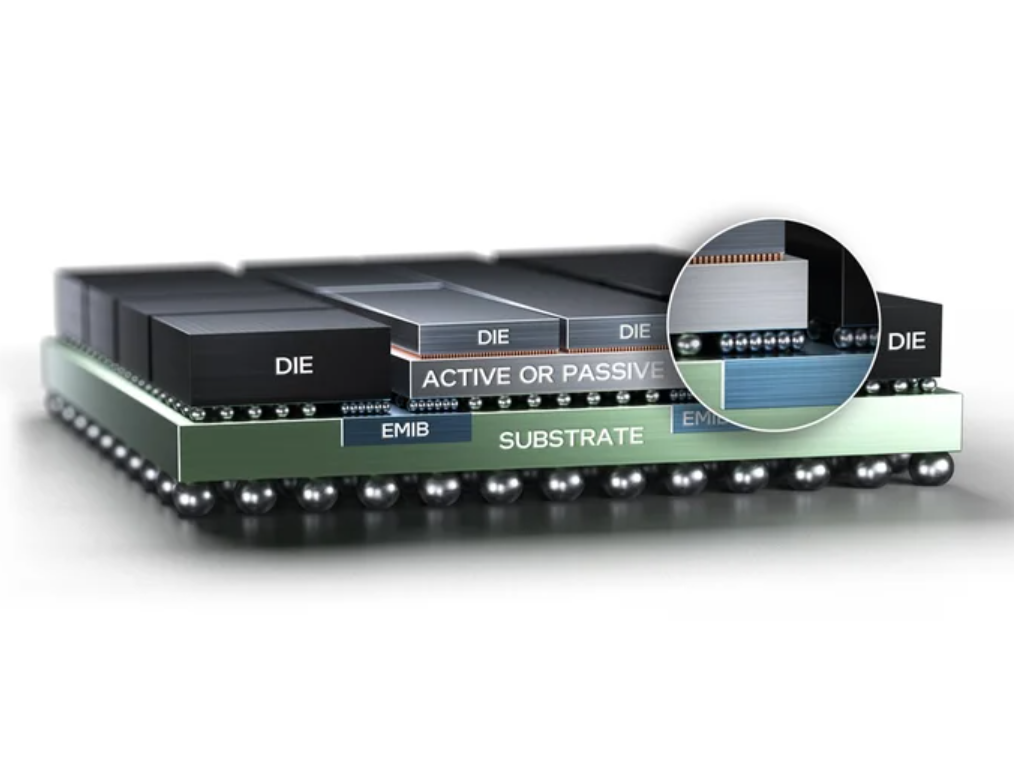

But, once set in place, they can be remarkably difficult to unseat. Take the semiconductor industry as an example. It’s geopolitical importance has directed billions of dollars towards re-creating a domestic US industry. But, it faces an uphill climb. After all, it’s not only a question of recreating the semiconductor manufacturing factories that have gone overseas, but also:

- the advanced and low-cost packaging technologies and vendors that are largely based in Asia

- the engineering and technician talent that is no longer really in the US

- the ecosystem of contractors and service firms that know exactly how to maintain the facilities and equipment

- the supply chain for advanced chemicals and specialized parts that make the process technology work

- the board manufacturers and ODMs/EMSs who do much of the actual work post-chip production that are also concentrated in Asia

A similar thing has happened in the life sciences CDMO (contract development and manufacturing organization) space. In much the same way that Western companies largely outsourced semiconductor manufacturing to Asia, Western biopharma companies outsourced much of their core drug R&D and manufacturing to Chinese companies like WuXi AppTec and WuXi Biologics. This has resulted in a concentration of talent and an ecosystem of talent and suppliers there that would be difficult to supplant.

Enter the BIOSECURE Act, a bill being discussed in the House with a strong possibility of becoming a law. It prohibits the US government from working with companies that obtain technology from Chinese biotechnology companies of concern (including WuXi AppTec and WuXi Biologics, among others). This is causing the biopharma industry significant anxiety as they are forced to find (and potentially fund) an alternative CDMO ecosystem that currently does not exist at the level of scale and quality as it does with WuXi.

According to [Harvey Berger, CEO of Kojin Therapeutics], China’s CDMO industry has evolved to a point that no other country comes close to. “Tens of thousands of people work in the CDMO industry in China, which is more than the rest of the world combined,” he says.

Meanwhile, Sound’s Kil says he has worked with five CDMOs over the past 15 years and is sure he wouldn’t return to three of them. The two that he finds acceptable are WuXi and a European firm.

“When we asked the European CDMO about their capacity to make commercial-stage quantities, they told us they would have to outsource it to India,” Kil says. WuXi, on the other hand, is able to deliver large quantities very quickly. “It would be terrible for anyone to restrict our ability to work with WuXi AppTec.”

Industry braces for Biosecure Act impact

Aayushi Pratap | C&EN