Despite the recent spotlight on the staggering $1.5 trillion in student debt that 44 million Americans owe in 2019, there has been surprisingly little discussion on how to measure the value of a college education relative to its rapidly growing price tag (which is the reason so many take on debt to pay for it).

While it’s impossible to quantify all the intangibles of a college education, the tools of finance offers a practical, quantitative way to look at the tangible costs and benefits which can shed light on (1) whether to go to college / which college to go to, (2) whether taking on debt to pay for college is a wise choice, and (3) how best to design policies around student debt.

The below briefly walks through how finance would view the value of a college education and the soundness of taking on debt to pay for it and how it can help guide students / families thinking about applying and paying for colleges and, surprisingly, how there might actually be too little college debt and where policy should focus to address some of the issues around the burden of student debt.

The Finance View: College as an Investment

Through the lens of finance, the choice to go to college looks like an investment decision and can be evaluated in the same way that a company might evaluate investing in a new factory. Whereas a factory turns an upfront investment of construction and equipment into profits on production from the factory, the choice to go to college turns an upfront investment of cash tuition and missed salary while attending college into higher after-tax wages.

Finance has come up with different ways to measure returns for an investment, but one that is well-suited here is the internal rate of return (IRR). The IRR boils down all the aspects of an investment (i.e., timing and amount of costs vs. profits) into a single percentage that can be compared with the rates of return on another investment or with the interest rate on a loan. If an investment’s IRR is higher than the interest rate on a loan, then it makes sense to use the loan to finance the investment (i.e., borrowing at 5% to make 8%), as it suggests that, even if the debt payments are relatively onerous in the beginning, the gains from the investment will more than compensate for it.

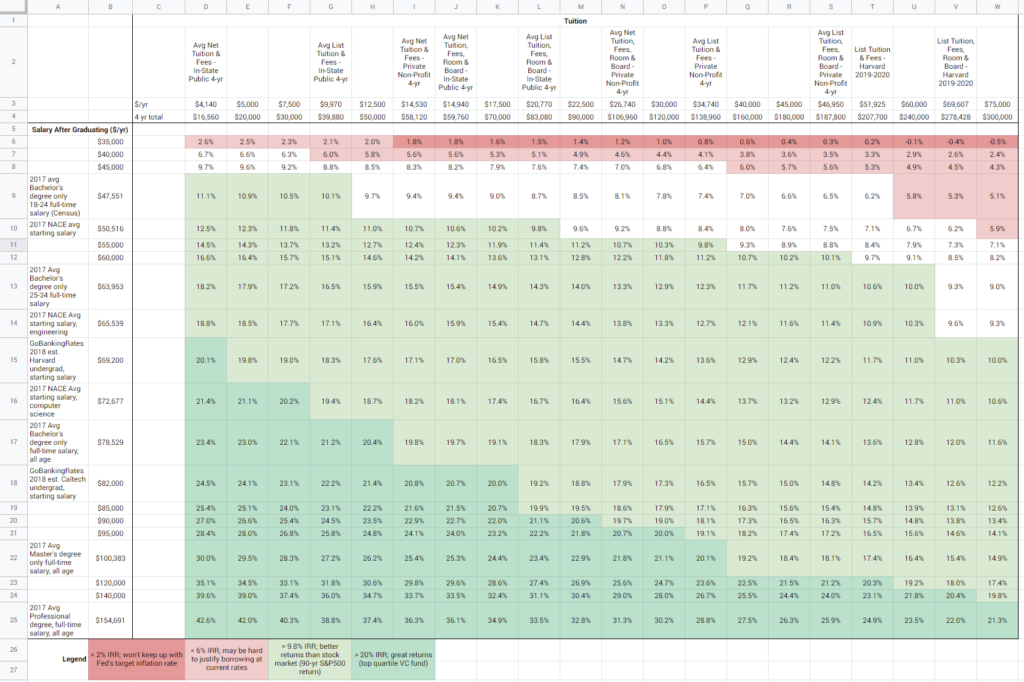

To gauge what these returns look like, I put together a Google spreadsheet which generated the figures and charts below (this article in Investopedia explains the math in greater detail). I used publicly available data around wages (from the 2017 Current Population Survey, GoBankingRate’s starting salaries by school, and National Association of Colleges and Employer’s starting salaries by major), tax brackets (using the 2018 income tax), and costs associated with college (from College Board’s statistics [PDF] and the Harvard admissions website). To simplify the comparisons, I assumed a retirement age of 65, and that nobody gets a degree more advanced than a Bachelor’s.

To give an example: if Sally Student can get a starting salary after college in line with the average salary of an 18-24 year old Bachelor’s degree-only holder ($47,551), would have earned the average salary of an 18-24 year old high school diploma-only holder had she not gone to college ($30,696), and expects wage growth similar to what age-matched cohorts saw from 1997-2017, then the IRR of a 4-year degree at a non-profit private school if Sally pays the average net (meaning after subtracting grants and tax credits) tuition, fees, room & board ($26,740/yr in 2017, or a 4-year cost of ~$106,960), the IRR of that investment in college would be 8.1%.

How to Benchmark Rates of Return

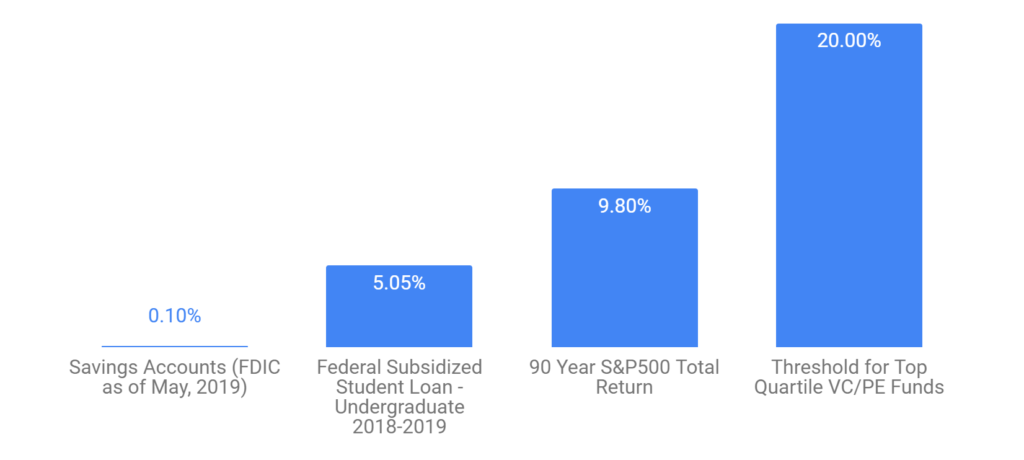

Is that a good or a bad return? Well, in my opinion, 8.1% is pretty good. Its much higher than what you’d expect from a typical savings account (~0.1%) or a CD or a Treasury Bond (as of this writing), and is also meaningfully higher than the 5.05% rate charged for federal subsidized loans for 2018-2019 school year — this means borrowing to pay for college would be a sensible choice. That being said, its not higher than the stock market (the S&P500 90-year total return is ~9.8%) or the 20% that you’d need to get into the top quartile of Venture Capital/Private Equity funds [PDF].

What Drives Better / Worse Rates of Return

Playing out different scenarios shows which factors are important in determining returns. An obvious factor is the cost of college:

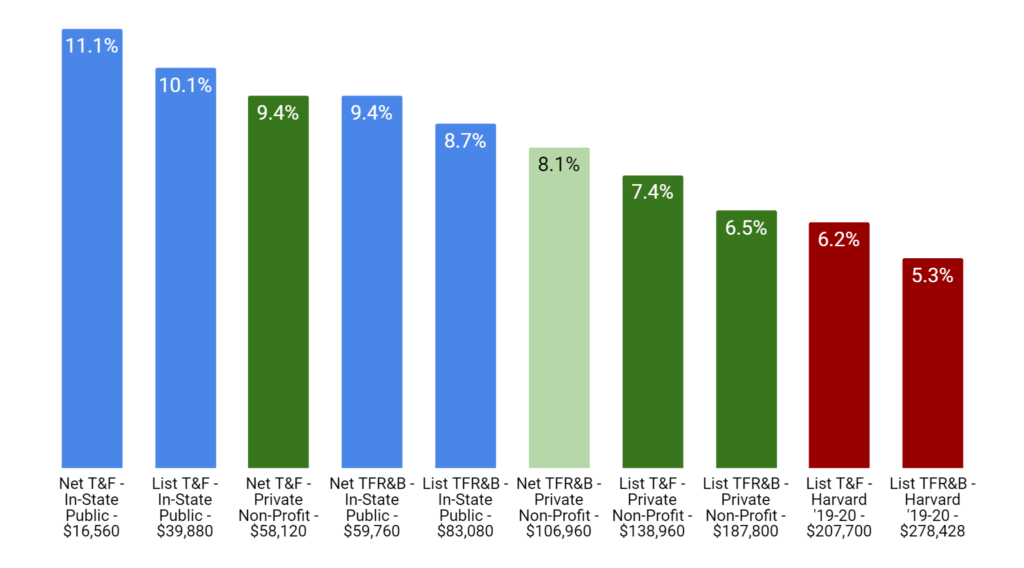

List: Average List Price; Net: Average List Price Less Grants and Tax Benefits

Blue: In-State Public; Green: Private Non-Profit; Red: Harvard

As evident from the chart, there is huge difference between the rate of return Sally would get if she landed the same job but instead attended an in-state public school, did not have to pay for room & board, and got a typical level of financial aid (a stock-market-beating IRR of 11.1%) versus the world where she had to pay full list price at Harvard (IRR of 5.3%). In one case, attending college is a fantastic investment and Sally borrowing money to pay for it makes great sense (investors everywhere would love to borrow at ~5% and get ~11%). In the other, the decision to attend college is less straightforward (financially), and it would be very risky for Sally to borrow money at anything near subsidized rates to pay for it.

Some other trends jump out from the chart. Attending an in-state public university improves returns for the average college wage-earner by 1-2% compared with attending private universities (comparing the blue and green bars). Getting an average amount of financial aid (paying net vs list) also seems to improve returns by 0.7-1% for public schools and 2% for private.

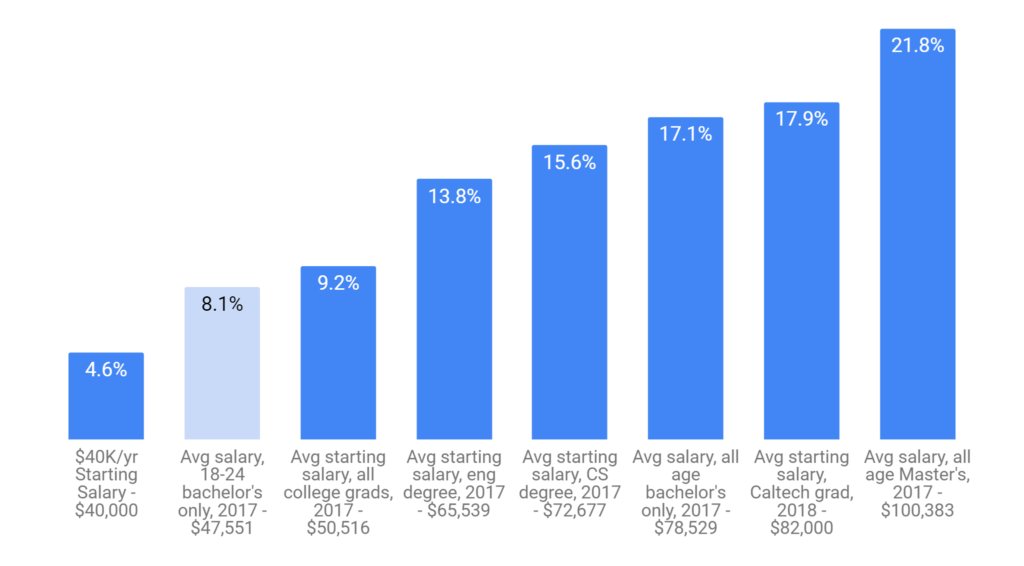

As with college costs, the returns also understandably vary by starting salary:

There is a night and day difference between the returns Sally would see making $40K per year (~$10K more than an average high school diploma holder) versus if she made what the average Caltech graduate does post-graduation (4.6% vs 17.9%), let alone if she were to start with a six-figure salary (IRR of over 21%). If Sally is making six figures, she would be making better returns than the vast majority of venture capital firms, but if she were starting at $40K/yr, her rate of return would be lower than the interest rate on subsidized student loans, making borrowing for school financially unsound.

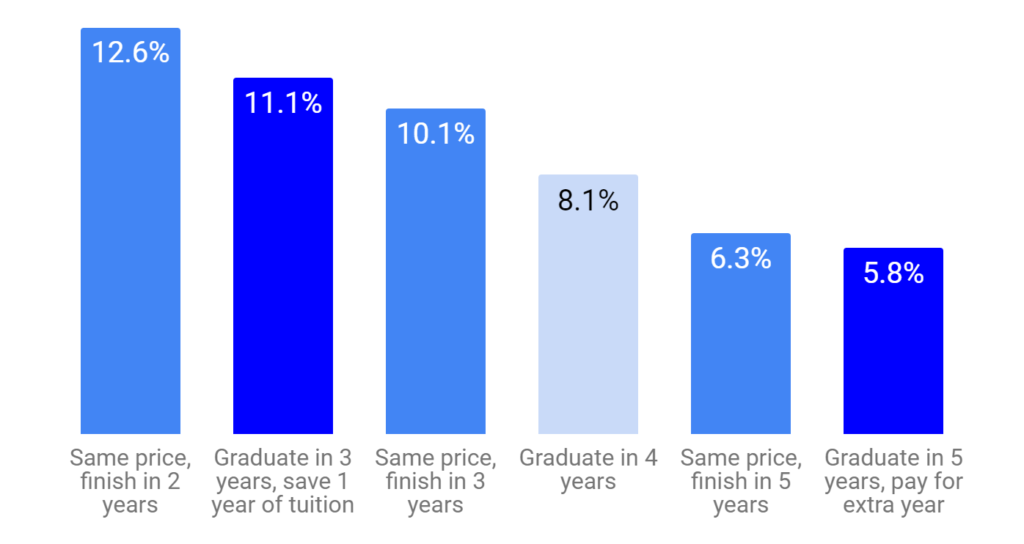

Time spent in college also has a big impact on returns:

Graduating sooner not only reduces the amount of foregone wages, it also means earning higher wages sooner and for more years. As a result, if Sally graduates in two years while still paying for four years worth of education costs, she would experience a higher return (12.6%) than if she were to graduate in three years and save one year worth of costs (11.1%)! Similarly, if Sally were to finish school in five years instead of four, this would lower her returns (6.3% if still only paying for four years, 5.8% if adding an extra year’s worth of costs). The result is that an extra / less year spent in college is a ~2% hit / boost to returns!

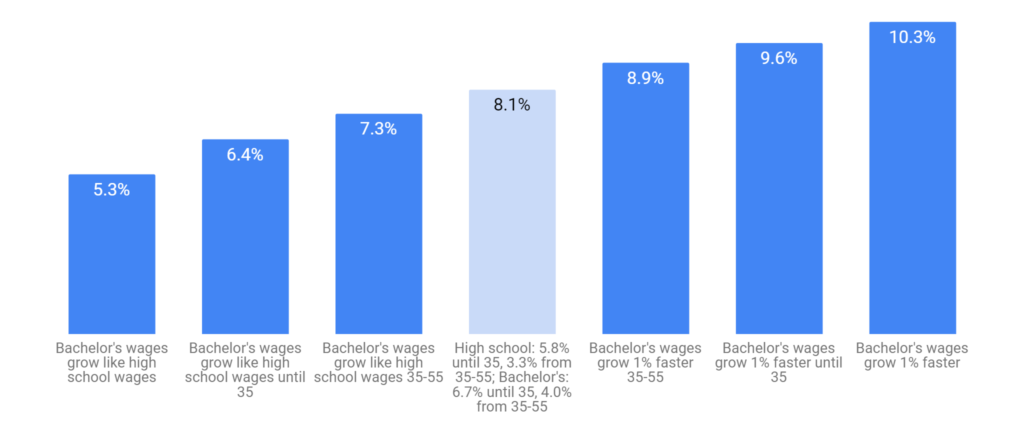

Finally, how quickly a college graduate’s wages grow relative to a high school diploma holder’s also has a significant impact on the returns to a college education:

Census/BLS data suggests that, between 1997 and 2017, wages of bachelor’s degree holders grew faster on an annualized basis by ~0.7% per year than for those with only a high school diploma (6.7% vs 5.8% until age 35, 4.0% vs 3.3% for ages 35-55, both sets of wage growth appear to taper off after 55).

The numbers show that if Sally’s future wages grew at the same rate as the wages of those with only a high school diploma, her rate of return drops to 5.3% (just barely above the subsidized loan rate). On the other hand, if Sally’s wages end up growing 1% faster until age 55 than they did for similar aged cohorts from 1997-2017, her rate of return jumps to a stock-market-beating 10.3%.

Lessons for Students / Families

What do all the charts and formulas tell a student / family considering college and the options for paying for it?

First, college can be an amazing investment, well worth taking on student debt and the effort to earn grants and scholarships. While there is well-founded concern about the impact that debt load and debt payments can have on new graduates, in many cases, the financial decision to borrow is a good one. Below is a sensitivity table laying out the rates of return across a wide range of starting salaries (the rows in the table) and costs of college (the columns in the table) and color codes how the resulting rates of return compare with the cost of borrowing and with returns in the stock market (red: risky to borrow at subsidized rates; white: does make sense to borrow at subsidized rates but it’s sensible to be mindful of the amount of debt / rates; green: returns are better than the stock market).

Except for graduates with well below average starting salaries (less than or equal to $40,000/yr), most of the cells are white or green. At the average starting salary, except for those without financial aid attending a private school, the returns are generally better than subsidized student loan rates. For those attending public schools with financial aid, the returns are better than what you’d expect from the stock market.

Secondly, there are ways to push returns to a college education higher. They involve effort and sometimes painful tradeoffs but, financially, they are well worth considering. Students / families choosing where to apply or where to go should keep in mind costs, average starting salaries, quality of career services, and availability of financial aid / scholarships / grants, as all of these factors will have a sizable impact on returns. After enrollment, student choices / actions can also have a meaningful impact: graduating in fewer semesters/quarters, taking advantage of career resources to research and network into higher starting salary jobs, applying for scholarships and grants, and, where possible, going for a 4th/5th year masters degree can all help students earn higher returns to help pay off any debt they take on.

Lastly, use the spreadsheet*! The figures and charts above are for a very specific set of scenarios and don’t factor in any particular individual’s circumstances or career trajectory, nor is it very intelligent about selecting what the most likely alternative to a college degree would be. These are all factors that are important to consider and may dramatically change the answer.

*To use the Google Sheet, you must be logged into a Google account; use the “Make a Copy” command in the File menu to save a version to your Google Drive and edit the tan cells with red numbers in them to whatever best matches your situation and see the impact on the yellow highlighted cells for IRR and the age when investment pays off

Implications for Policy on Student Debt

Given the growing concerns around student debt and rising tuitions, I went into this exercise expecting to find that the rates of return across the board would be mediocre for all but the highest earners. I was (pleasantly) surprised to discover that a college graduate earning an average starting salary would be able to achieve a rate of return well above federal loan rates even at a private (non-profit) university.

While the rate of return is not a perfect indicator of loan affordability (as it doesn’t account for how onerous the payments are compared to early salaries), the fact that the rates of return are so high is a sign that, contrary to popular opinion, there may actually be too little student debt rather than too much, and that the right policy goal may actually be to find ways to encourage the public and private sector to make more loans to more prospective students.

As for concerns around affordability, while proposals to cancel all student debt plays well to younger voters, the fact that many graduates are enjoying very high returns suggests that such a blanket policy is likely unnecessary, anti-progressive (after all, why should the government zero out the costs on high-return investments for the soon-to-be upper and upper-middle-classes), and fails to address the root cause of the issue (mainly that there shouldn’t be institutions granting degrees that fail to be good financial investments). Instead, a more effective approach might be:

- Require all institutions to publish basic statistics (i.e. on costs, availability of scholarships/grants, starting salaries by degree/major, time to graduation, etc.) to help students better understand their own financial equation

- Hold educational institutions accountable when too many students graduate with unaffordable loan burdens/payments (i.e. as a fraction of salary they earn and/or fraction of students who default on loans) and require them to make improvements to continue to qualify for federally subsidized loans

- Making it easier for students to discharge student debt upon bankruptcy and increasing government oversight of collectors / borrower rights to prevent abuse

- Government-supported loan modifications (deferrals, term changes, rate modifications, etc.) where short-term affordability is an issue (but long-term returns story looks good); loan cancellation in cases where debt load is unsustainable in the long-term (where long-term returns are not keeping up) or where debt was used for an institution that is now being denied new loans due to unaffordability

- Making the path to public service loan forgiveness (where graduates who spend 10 years working for non-profits and who have never missed an interest payment get their student loans forgiven) clearer and addressing some of the issues which have led to 99% of applications to date being rejected

Special thanks Sophia Wang, Kathy Chen, and Dennis Coyle for reading an earlier version of this and sharing helpful comments!

Thought this was interesting or helpful? Check out some of my other pieces on investing / finance.

Leave a Reply