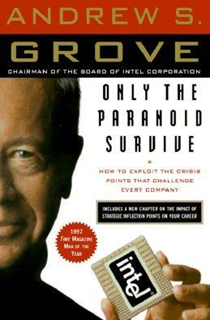

Knowing my interest in tech strategy, a coworker recommended I pick up HBS professor Clayton Christensen’s “classic” book on disruptive innovation: The Innovator’s Dilemma. And, I have to say I was very impressed.

The book tries to answer a very interesting question: why do otherwise successful companies sometimes fail to keep up on innovation? Christensen’s answer is counter-intuitive but deep: the very factors that make a company successful, like listening to customer needs, make it difficult for successful companies to adopt disruptive innovations which create new markets and new capabilities.

This sounds completely irrational, and I was skeptical when I first heard it, but Christensen makes a very compelling case for it. He begins the book by considering the hard disk drive (HDD) industry. The reason for this is, as Christensen puts it (and this is merely page one of chapter one!):

“Those who study genetics avoid studying humans, because new generations come along only every thirty years or so, and so it takes a long time to understand the cause and effect of any changes. Instead, they study fruit flies, because fruit flies are conceived, born, mature, and die all within a single day. If you want to understand why something happens in business, study the disk drive industry. Those companies are the closest things to fruit flies that the business world will ever see.”

From that oddly compelling start, Christensen applies multiple techniques to establish the grounds for his theory. He begins by admitting that his initial hypothesis for why some HDD companies successfully innovated had nothing to do with his current explanation and was something he called “the technology mudslide”: that because technology is constantly evolving and shifting (like a mudslide), companies which could not keep moving to stay afloat (i.e. by innovating) would slip and fall.

But, when he investigated the different types of technological innovations which hit the HDD industry, he found that the large companies were actually constantly innovating, developing new techniques and technologies to improve their products. Contrary to the opinion of many in the startup community, big companies did not lack innovative agility – in fact, they were the leaders in developing and acquiring the successful technologies which allowed them to make better and better products.

But, every now and then, when the basis of competition changed, like the shift to a smaller hard disk size to accommodate a new product category like minicomputers versus mainframes or laptops versus desktops, the big companies faltered.

From that profound yet seemingly innocuous observation grew a series of studies across a number of industries (the book covers industries ranging from hardcore technology like hard disk drives and computers to industries that you normally wouldn’t associate with rapid technological innovation like mechanical excavators, off-road motorbikes, and even discount retailing) which helped Christensen come to a basic logical story involving six distinct steps:

- Three things dictate a company’s strategy: resources, processes, and values. Any strategy that a company wishes to embark on will fail if the company doesn’t have the necessary resources (e.g. factories, talent, etc.), processes (e.g. organizational structure, manufacturing process, etc.), and values (e.g. how a company decides between different choices). It doesn’t matter if you have two of the three.

- Large, successful companies value listening to their customers. Successful companies became successful because they were able to create and market products that customers were willing to pay for. Companies that didn’t do this wouldn’t survive, and resources and processes which didn’t “get with the program” were either downsized or re-oriented.

- Successful companies help create ecosystems which are responsive to customer needs. Successful companies need to have ways of supporting their customers. This means they need to have or build channels (e.g. through a store, or online), services (e.g. repair, installation), standards (e.g. how products are qualified and work with one another), and partners (e.g. suppliers, ecosystem partners) which are all dedicated towards the same goal. If this weren’t true, the companies would all either fail or be replaced by companies which could “get with the program.”

- Large, successful companies value big opportunities. If you’re a $10 million company, you only need to generate an extra $1 million in sales to grow 10%. If you’re a $10 billion company, you need to find an extra $1 billion in sales to grow an equivalent amount. Is it any wonder, then, that large companies will look to large opportunities? After all, if companies started throwing significant resources or management effort on small opportunities, the company would quickly be passed up by its competitors.

- Successful companies don’t have the values or processes to push innovations aimed at unproven markets, which serve new customers and needs. Because successful companies value big opportunities which meet the needs of their customers and are embedded in ecosystems which help them do that, they will mobilize their resources and processes in the best way possible to fulfill and market those needs. And, in fact, that is what Christensen saw – in almost every market he studied, when the customers of successful companies needed a new feature or level of quality, successful companies were almost always successful at either leading or acquiring the innovation necessary to do that. But, when it came to experimental products offering slimmer profit margins and targeting new customers with new needs and new ecosystems in unproven markets, successful companies often failed, even if management made those new markets a priority, because those companies lacked the values and/or processes needed. After all, if you were working in IBM’s Mainframe division, why would you chase the lower-performance, lower-profit minicomputer industry and its unfamiliar set of customers and needs and distribution channels?

- Disruptive innovations tend to start as inferior products, but, over time improve and eventually displace older technologies. Using the previous example, while IBM’s mainframe division found it undesirable to enter the minicomputer market, the minicomputer players were very eager to “go North” and capture the higher performance and profitability that the mainframe players enjoyed. The result? Because of the values of the mainframe players as compared with the values of the minicomputer players, minicomputer companies focused on improving their technology to both service their customer’s needs and capture the mainframe business, resulting in one disruptive innovation replacing an older one.

The most interesting thing that Christensen pointed out was that, in many cases, established companies actually beat new players to a disruptive innovation (as happened several times in the HDD and mechanical excavator industries)! But, because these companies lacked the necessary values, processes, and ecosystem, they were unable to successfully market them. Their success actually doomed them to failure!

But Christensen doesn’t stop with this multi-faceted and thorough look at why successful companies fail at disruptive innovation. He spends a sizable portion of the book explaining how companies can fight the “trappings” of success (i.e. by creating semi-independent organizations that can chase new markets and be excited about smaller opportunities), and even closes the book with an interesting “ahead-of-his-time” look (remember, this book was written over a decade ago!) at how to bring about electric cars.

I highly recommend this book to anyone interested in the technology industry or even, more broadly speaking, on understanding how to think about corporate strategy. While most business books on this subject use high-flying generalizations and poorly evaluated case studies, Christensen approaches each problem with a level of rigor and thoroughness that you rarely see in corporate boardrooms. His structured approach to explaining how disruptive innovations work, who tends to succeed at them, why, and how to conquer/adapt to them makes for a fascinating read, and, in my humble opinion, is a great example of how corporate strategy should be done – by combining well-researched data and structured thinking. To top it all, I can think of no higher praise than to say that this book, despite being written over a decade ago, has many parallels to strategic issues that companies face today (i.e. what will determine if cloud computing on netbooks can replace the traditional PC model? Will cleantech successfully replace coal and oil?), and has a number of deep insights into how venture capital firms and startups can succeed, as well as some insights into how to create organizations which can be innovative on more than just one level.

Book: The Innovator’s Dilemma by Clayton Christensen

Thought this was interesting? Check out some of my other pieces on Tech industry